Mayumi Fukushima is a PhD student in Political Science.

WITH A LAME-DUCK president in office, the modus operandi for U.S. diplomacy toward Asia this year may be simply to avoid any negative outcomes and expend minimum effort. Since the crisis in Ukraine flared up, the Obama administration has been pressuring Japan not to pursue a rapprochement with Russia. Yet Prime Minister Shinzo Abe had a summit meeting with President Putin in Sochi, a resort town in southwestern Russia, in early May. Abe has been encouraging Putin to visit Japan before the end of this year in order for the two leaders to resolve long-pending territorial disputes between their countries once and for all. Doing so, Abe hopes, should improve security environments in the northern area of Japan and allow Tokyo to concentrate its military resources on patrolling the East and South China Seas. As Figure 1 shows, Russian forces have accounted for more than half of foreign aircraft against which Japanese Air Self-Defense Force scrambled because they were threatening or violating Japanese airspace. More importantly, Russian military aircraft have recently become increasingly active, as China grows more assertive in areas surrounding Japan. And as is clear in Figure 2, Russian military aircraft appear to be threatening Japanese airspace from all directions.

Under such circumstances, it is understandable that Japan wants to do something to improve its security environments. In the meantime, Russia is growing increasingly close to and dependent on China. Indeed, the familiar Sino-Russian relationship of decades ago has been turned on its head. The single state most affected by this change is perhaps Japan. At least for the time being, Russia's weakness vis-à-vis China actually renders a comprehensive territorial agreement between Tokyo and Moscow extremely unlikely for reasons I will discuss below. Japan therefore should shelve its territorial disputes and instead strike a more limited bargain with Russia, so that it can focus on the main threat of China.

Sino-Russian Political and Military Relations

Journalists often call Russia and China "frenemies." On the one hand, their political and military relationships have appeared to grow closer than ever. Chinese President Xi Jinping chose Russia as the first country to visit on becoming president in 2013. All of their territorial disputes had been resolved by 2015. The two countries conducted large-scale joint naval exercises dubbed "Joint Sea 2015" in the Mediterranean Sea and off Vladivostok. Moscow and Beijing seem to have shared interests in undermining the U.S. military presence in Asia: just recently the two countries simultaneously opposed a planned deployment of the anti-ballistic missile system called Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) in South Korea.

On the other hand, their vast common land border is a constant source of mistrust, as the Russian side is sparsely populated and rich with raw materials, the Chinese side full of people. Many of Russia's tactical nuclear weapons are pointed at China. It is true that China and Russia are still tussling for influence, especially in Central Asia and the Arctic Ocean. Russia warily watches China's "One Belt, One Road" policy, which seeks to consolidate Beijing's influence over Central Asia. China's maritime expansion into the Arctic Ocean seems to be another source of concern for Russia, as China develops a new route for seaborne transportation going through Russian territorial or contiguous waters in the Arctic Ocean.

Sino-Russian Economic Relations

The concept of "frenemies" is at odds with Sino-Russian economic relations, however. The two countries' trade volume quadrupled between 2004 and 2014, with a record of $95 billion in 2014. While it dropped by 27.8% to $64 billion in 2015 due to a worldwide economic disruption, it is still three times their trade volume in 2004. Russia exports far more oil to China than ever before through a recently constructed ESPO pipeline, which goes from Eastern Siberia toward the Pacific Ocean. China and Russia struck a gas deal worth $400 billion in May 2014 for Russia's Gazprom to supply Siberian gas to China through a pipeline between 2018 and 2048.

But looking at their respective lists of other important trade partners gives us a different picture of their economic relations. From the Russian perspective, China is by far its biggest trading partner in the world, followed by the Netherlands and Germany, whereas from the Chinese perspective Russia is just the ninth largest trading partner. China's most important trading partners are the United States, Hong Kong, and Japan. Most of China's fuel supplies come from Australia and the Middle East, and Russia's share in the Northeast Asian gas market is unlikely to exceed 3% in the next decade and by 2030 will be no more than 9%. As long as Russia remains a resource-based economy with its underdeveloped service sector, we should expect its dependence on China to continue. This is why China squeezed such a favorable gas deal out of Russia's Gazprom in 2014.

Overall Sino-Russian Relations

How do we understand overall Sino-Russian relations, then? Russian economic dependence on China seems to largely override any tendency of "frenemies" competing for larger influence in Central Asia and the Arctic Ocean.

Russia's economic problems, especially those in Russia's Far East, are far more serious than the problem of Russia's declining status as a military power. In 2014, as the price of oil collapsed, the countries of central and eastern Europe continued to wean themselves off Russian gas. Slow global growth further reduced the appetite for Russian natural resources, and the West imposed sanctions on Moscow in the aftermath of Crimea. The ruble lost nearly half of its value against the U.S. dollar since 2014, and the Russian economy was shrinking by nearly four percent in 2015.

As Russia's economic problems run deep, President Putin seems increasingly concerned about the Russian Far East, where its population dropped by more than 20% since 1990 and is holding the Russian economy back. In addition, economic stagnation in regions far from Russia's center could have politically destabilizing effects, which President Putin fears most. All of these problems leave President Putin with few options other than to rely on China. As long as record-low oil prices and the West's economic sanctions against Russia persist, Moscow cannot afford to lose the Chinese market.

Implications of the Current Sino-Russian Relations for Japan

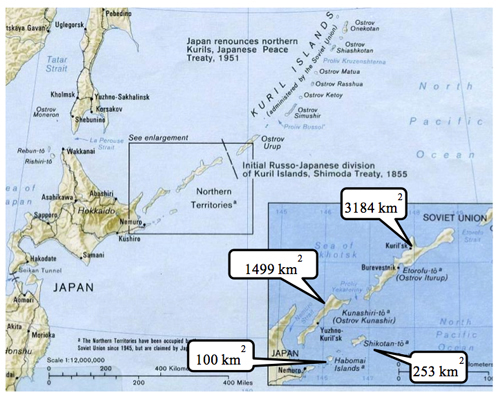

Unfortunately, the single state most affected by recent changes in Sino-Russian relations is perhaps Japan. Since the Cold War ended, Japanese leaders have consistently sought to resolve territorial disputes with Russia regarding the so-called Northern Territories (hopporyodo) (See the map below) in order to conclude a Russian-Japanese peace treaty. In particular, the current prime minister, Abe, appears much more determined than his predecessors to achieve a diplomatic breakthrough with Russia.

What explains Abe's determination? First, he seems to assume that given Russia's isolation after the crisis of Crimea, President Putin is currently more willing than he would be otherwise to make significant concessions in order to find reliable friends. Second, Abe believes that improved bilateral relations between Russia and Japan would have restraining effects on China's ever-increasing maritime adventurism. Indeed, in the face of President Obama's concerns, Tokyo justifies its high-level contacts with Moscow in the midst of the crisis in Ukraine with the logic of balancing: Better relations between Moscow and Tokyo could prevent Russia from getting too close to China. Finally, Abe sees a window of opportunity opening in Japanese politics. Since Abe came to power in 2012, political opposition has been weak. As any peaceful resolution of the territorial disputes with Russia would require significant concessions from the Japanese side, powerful opposition parties would make it more difficult even for someone labeled a nationalist, such as Abe, to justify concessions. With the same rationale, Tokyo also hopes that President Putin's high approval ratings in Russia equip him to make big concessions.

Perhaps Abe is right to assume that President Putin covets closer relations with Japan. From the Russian perspective, this could improve Moscow's bargaining position vis-à-vis China as Russia grows uncomfortably dependent on the Chinese market. However, Tokyo seems to turn a blind eye to the inconvenient truth that, given Moscow's economic dependence on Beijing and its understandable desire to somehow restore its diplomatic standing vis-à-vis Beijing, the strategic value for Russia of the Northern Territories is actually increasing. This is especially true given China's maritime expansion into the Arctic Ocean. It is therefore unlikely that Japan could resolve the territorial disputes on its term anytime soon. No matter how popular President Putin has been in Russia, Tokyo should not expect him to make big concessions over the territorial disputes.

This, however, does not mean the chance of success will be nil for Japan's bid to take any part of the Northern Territories back. Russia might offer the return of two small southern islands, Habomai and Shikotan, that account for less than 10% of the total geographic area under dispute, just like Moscow did sixty years ago. In fact, while the two countries normalized diplomatic relations in 1956, they failed to sign a peace treaty because Japan was not satisfied with Moscow's paltry offer.

Would Abe be able to convince the Japanese public that the return of the two small islands was the best the Japanese could hope for? If not, Japan would be wise to let sleeping dogs lie. Considering the growing threat from China, however, it still makes sense for Japan to reach some sort of agreement with Russia to stabilize the security environment in the northern area as soon as possible. That way, Tokyo can allocate more military resources in the East and South China Seas. By doing so, it could bide its time on the territorial disputes, waiting for a moment when Russia becomes less dependent on China economically.