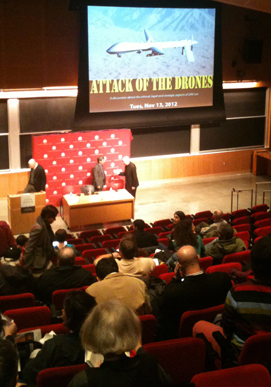

Attack of the Drones

The Starr Forum "Attack of the Drones" was held on Nov 13, 2012. A video of the event is available here

ON TUESDAY, November 13, the Center for International Studies at MIT and the MIT Technology and Culture Forum co-sponsored the Starr Forum: Attack of the Drones.

The speakers included Barry Posen, Ford International Professor of Political Science, MIT; Director, MIT Security Studies Program; Rabia Mehmood, Correspondent and Producer, Express; Bryan Hehir, Parker Gilbert Montgomery Professor of the Practice of Religion and Public Life, Harvard Kennedy School of Government and Secretary for Health Care and Social Services in the Archdiocese of Boston. Moderating the discussion was Kenneth Oye, Associate Professor of Political Science and Engineering Systems and Director, MIT Program on Emerging Technologies.

The panel represented a wide array of perspectives, touching on the technical, ethical, and political consequences of the increased use of drones by the United States.

Barry Posen began the discussion by providing a technical analysis of the unmanned aerial systems (UAVs) that are generally associated with US engagements in Afghanistan and Pakistan followed by an analysis of the legal and strategic concerns that undergird debates about the use of drones.

The drones primarily used by the US in Southeast Asia are the Predator and Reaper models, neither of which is particularly fast or stealthy. Traditionally, these types of drones have been used for reconnaissance and surveillance, until recently when precision guided missiles were integrated into the systems.

The primary technical benefit of drones is their ability to travel to an area and hover for an exceptionally long time, without falling victim to pilot fatigue or other human limitations. The level of resolution on many of these systems is state-of-the-art, and the precision of their missile systems is quite good. The current arsenal of drones allows the military to have eyes around the world for extended periods of time. However, "unmanned" is a bit of a misnomer—there are rotational operating crews of 15-20 soldiers tasked with operating, monitoring, and assessing the drones and the information that they produce. All of these features allow for a highly controlled mission—the time constraints are much broader, which allows for more decisive targeting and analysis. Finally, the notion that all of these can be achieved with no soldiers on the ground makes this technology doubly appealing.

The issues associated with drone warfare are of two types: the first relates to the laws of war and violations of international law, and the second relates to the principles of proportionality and distinction. On the international law side of things, the general impression is that US lawyers have been able to guard against questions of sovereignty and violations of international laws. However, violations of the principles of proportionality and distinction must be considered on a more specific basis. That said, drone systems do appear to make these considerations of proportionality and distinction easier—by providing more time and clear pictures of the situation on the ground, soldiers have more accurate information on which they can base their decisions.

Though critics often argue that drones have resulted in an unacceptably high rate of civilian casualties, the standard of past wars makes us look more favorably on drone technology. While estimates of civilian causalities from drone strikes do vary, the New America Foundation recently reported that in the 2004-2012 period only 15% of drone casualties have been non-militant casualties—approximately 500 people—and in 2012 the rate was down to 1%. By comparison, shelling in France during World War II resulted in nearly 70,000 French civilian deaths.

In addition to the technical and legal questions raised by the use of drones, Posen also discussed two of the primary strategic issues involved in drone warfare. First, he noted that insurgents in Afghanistan and Pakistan have proven fairly resilient, even in the face of stepped-up drone strikes. This has raised questions about the strategic effectiveness of the strikes. When combined with the potential public image drawbacks, these strategic concerns become even more pressing. Fundamentally, drone strikes kill people, and in doing so, the US alienates the friends, family, and (at times) the broader public of states where drones are operating. While most students of war would argue that civilian causalities from drone strikes have been relatively low, the general public may not readily recognize this fact. Thus, while the technical utility of drones may be high, it should be tempered by acknowledging some of the strategic challenges, as well as its potential for overuse.

According to Rabia Mehmood, who joined the discussion via a pre-recorded video interview with Kenneth Oye, the Pakistani media has presented two different images of the drone attacks—official channels have focused on the killing of militants, whereas non-state media has begun to expose some of the more graphic footage of drone strikes, as well as the civilian impact. Generally, the latter footage and reporting comes from activists in the local population.

Five years ago there appears to have been an informal understanding between President Pervez Musharraf, the Pakistani military, and the United States regarding the operation of US drones in Pakistani soil. In fact, it is largely an open secret that Musharraf was a proponent of this technology. More recently, the civilian government has framed the argument in such a way that places the blame on the United States, but Pakistan's capacity to combat terrorism unilaterally remains a concern in the international community. However, politicians like Imram Khan have gotten a great deal of political mileage out of their opposition to US drone attacks.

Ideally, the Pakistani Army would like to obtain and operate drone technology on their terms, in large part because the US is targeting groups that are operating involved in the Afghan insurgency, rather than those who create a direct threat to Pakistan. In an effort to make a compelling argument to the US that they can successfully operate the drones, the Pakistani army has pointed to their effective use of F-16 jets.

Generally, however, Mehmood said that the political mood in the country is that of condemning the strikes. Most major political parties are aggressively speaking out against US strikes, while emphasizing that they should be in charge of taking care of the terrorist threat within their borders. In general, the political parties will admit that terrorism is a problem but demand that the Pakistani government be in charge of the technology used to address it.

The notion of extrajudicial killings remains peripheral to the debate about drones in Pakistan. Instead, the focus largely remains on civilian deaths and the violations of sovereignty. While there is a diversity of views related to the drone attacks (with some even supporting US oversight) there is little room for in-depth debate in the media, concluded Mehmood.

Brian Hehir began his discussion with a review of the broad spectrum of ethical views that can be brought to bear on questions of war and technology. In particular, he noted that there are two extreme evaluations of war ethics that provide the bookends of analysis. The first is that all war is ethically wrong, which precludes any use of force on another human being. At the opposite extreme is the morality of Thucydides, who argues that the nature of war is such that there cannot be any morality. In between these two positions, however, is a third argument, where the state must justify the use of forces each time it engages in that behavior. Under this position, the burden of proof lies in the aggressor. Moreover, one must ask not just who has the authority to make these decisions, but also when and why the use of force can be justified.

The use of drones brings to the fore a larger debate about the means and ends of modern, transnational warfare. Specifically, drones significantly expand the arsenal of US military capability, while simultaneously insulating it against the risk of hurting its own citizens. In addition, the privatization of war, in which the United States' enemies are private actors, who find havens around the world, has allowed the US to see the world as a single battlefield. The use of drones has been a manifestation of that inclination, and has permeated the borders of allies and sovereign nations alike. Without better defining the battlefield, the US will find itself challenged to find coherent answers about the means of warfare insofar as it lacks a clear picture of the ends of warfare. These are difficult questions that must be guided by principle.

While Hehir acknowledged that the precision of drone attacks also has the potential to limit damages associated with these attacks, the insulation of remote operation raises concerns about whether the US is sufficiently engaged in the reality of drone operations. But while these technical questions should be considered, they are not new to the study of war. However, Hehir makes the important point that there are larger strategic questions about the globalization of battle that are unique to the 21st century.

The question and answer portion of the Starr Forum focused primarily on the vetting and decision making process for drone targeting. While neither of the panelists felt that the United States was likely to go about this process cavalierly, they noted the importance of civilian oversight and inquiry into these matters. By applying ethical lenses and continuing to ask policymakers for information, civilians are in a position to check overuse and misuse of this technology. Finally, the panelists added that while Pakistan may only provide implicit support for the drone attacks, other states—like Yemen—are more supportive of the US presence.

Lena Andrews served as rapporteur for this talk.

Journalist from India Joins CIS

Priyanka Borpujari

PRIYANKA BORPUJARI, an independent journalist based in Mumbai, India, was selected as the 2012-13 Elizabeth Neuffer Fellow. Borpujari is the eighth recipient of the annual fellowship, which gives a woman journalist working in print, broadcast or online media the opportunity to build skills while focusing exclusively on human rights journalism and social justice issues. The award is offered through the International Women's Media Foundation (IWMF) and is sponsored in part by the Center for International Studies at MIT.

Borpujari is spending the seven-month fellowship as a research associate at CIS. She will also complete internships at The Boston Globe and The New York Times. Borpujari will explore topics such as malnutrition, hunger, displacement and violence, especially in light of India's surging gross domestic product. She would like to "return home to report … in a better, stronger way, which would hopefully have an impact on policies, or at least in the way we perceive development."

Borpujari, 27, has worked as a reporter for six years for publications including Mumbai Mirror, The Asian Age and exchange4media.com. Since launching her freelance career three years ago, she has focused on the plight of indigenous groups that are being systematically displaced from their land.

Borpujari reported on the ways in which indigenous populations in the state of Chhattisgarh were being caught in a war between a government keen on displacing them to make way for mines and factories, and armed Maoists. Her reports brought focus to what she describes as "deprived, malnourished, burning India," even as false police charges were levied against her in an attempt to keep her away from reporting in the region. She says she has "attempted to uncover the gory hidden civilian war for resources in India, which is often ignored by the mainstream media, in its rush to portray a shining, emerging economy."

"We are honored to have Priyanka with us. Her work as a human rights journalist is informative and admirable. We hope her time in an academic setting adds to the achievement of her noble goals," said Richard Samuels, director of the Center for International Studies and Ford International Professor of Political Science at MIT.

Former Special Advisor to Japan PM Joins CIS

Yukio Okamoto

YUKIO OKAMOTO, a former special advisor to the prime minister of Japan, has been named a 2012-13 Robert E. Wilhelm Fellow.

From 1968 to 1991 Okamoto was a career diplomat in Japan's Ministry of Foreign Affairs. His overseas postings included stints in Paris at the OECD and in the embassies in Cairo and Washington. He retired from the Ministry in 1991 and established Okamoto Associates Inc., a political and economic consultancy.

Post-retirement, Okamoto has served in a number of advisory positions. From 1996 to 1998, he was Special Advisor to Prime Minister Ryutaro Hashimoto. From October 2001 to March 2003, he was Special Advisor to the Cabinet. From March 2003 to March 2004, he was Special Advisor on Iraq to Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi. Concurrent with the above last two posts he was Chairman of the Prime Minister's Task Force on Foreign Relations. Until September of 2008 he was a member of Prime Minister Yasuo Fukuda's Study Group on Diplomacy.

Okamoto is an adjunct professor of international relations at Ritsumeikan University. He sits on the Board of Directors of several multinational companies. He is the president of Shingen'eki Net, a non-profit group for active seniors with 16,000 members.

Okamoto has written books on Japanese diplomacy and government and is a regular contributor to major newspapers and magazines. Okamoto is a well-known public speaker and a frequent guest on public affairs and news broadcasts.

"Yukio Okamoto brings to MIT an unparalleled set of experiences on the world stage. The Center is delighted to have him with us to continue his research and writing, and to work with students and faculty through the next academic year," said Richard Samuels, director of the Center for International Studies and Ford International Professor of Political Science.

A generous gift from Robert E. Wilhelm supports the Center's Wilhelm fellowship. The fellowship is awarded to individuals who have held senior positions in public life and is open, for example, to heads of non-profit agencies, senior officials at the State Department or other government agencies, including ambassadors, or senior officials from the UN or other multilateral agencies. Previous Wilhelm Fellows include: Naomi Chazan, the former Deputy Speaker of the Israeli Knesset, Ambassador Barbara Bodine, Ambassador Frances Deng, and Admiral William Fallon.