Former National Security Advisor of India Joins CIS

Shivshankar Menon

Shivshankar Menon, a former national security advisor of India, was a Robert E. Wilhelm fellow at CIS for one month beginning February 3, 2015.

Menon's career with the Indian Foreign Service began in 1972. He served the Department of Atomic Energy as advisor to the Atomic Energy Commission. He continued this work after being posted in Vienna. Then he held three posts in Beijing. The final position in China he served as ambassador. He has also served as ambassador to Israel and high commissioner to Sri Lanka and Pakistan. He was appointed foreign secretary in 2006, and was the national security adviser to Prime Minister Manmohan Singh. His term as national security adviser ended in May 2014.

During his time at MIT, Menon worked on a history of India-China relations. He also meet with faculty and students to discuss regional issues.

CIS director Richard Samuels welcomed Menon: "My colleagues and I are thrilled that the former national security advisor of India accepted our invitation to MIT."

A generous gift from Robert E. Wilhelm supports the Center's Wilhelm fellowship. The fellowship is awarded to individuals who have held senior positions in public life and is open, for example, to heads of non-profit agencies, senior officials at the State Department or other government agencies, including ambassadors, or senior officials from the UN or other multilateral agencies. Previous Wilhelm fellows include: Ambassador Barbara Bodine, Ambassador Frances Deng, Admiral William Fallon, and Yukio Okamoto, a former special advisor to the prime minister of Japan.

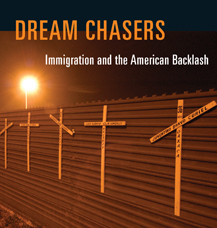

Culture Clash: New Book Explores Fierce Debates Over Immigration

by Peter Dizikes, MIT News Office | Originally published here

Dream Chasers: Immigration and the American Backlash by John Tirman. Published March 2015 by MIT Press.

Immigration policy has been among the most rancorous of U.S. political issues in recent years. What has been fueling America's contentious debates over the topic?

Security, according to many people: In the time since the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, keeping borders secure has been a main justification for tightly controlled immigration. But underneath those concerns lies a simmering cultural clash, according to one MIT scholar who has been studying the topic in depth recently.

"It's about some larger loss of U.S. identity," says John Tirman, executive director of MIT's Center for International Studies. Opponents of immigration, he adds, "say they're not concerned about culture, use of language, and changing norms, but I think it really does come down to those kinds of issues."

And in the last two decades, Tirman thinks, that has specifically meant a fight about the relationship between U.S. identity and Latin American culture, in light of the large numbers of Latino immigrants who have come to the country. Disputes about language use, school curricula, and other cultural issues have made this evident, Tirman says.

"The way the reaction to illegal immigration has manifested indicates most clearly that the resistance is mainly one of cultural difference and exclusion … rather than economics or politics," writes Tirman in his new book on the subject, Dream Chasers, just published by the MIT Press.

Class Conflict

While Tirman says there are many places to find these cultural clashes over immigration, his book focuses on a few case studies, such as an educational dispute that spilled into the state legislature in Arizona. In Tucson, some schools adopted a Mexican-American Studies (MAS) program teaching the region's history from an alternate point of view, with a much greater emphasis on the historic presence of Mexicans in the area, and a more critical interpretation of U.S. actions.

The MAS program seemed to have a beneficial effect on Latino students, keeping them engaged and helping their academic standing. But by 2010, the state's superintendent of schools and legislators effectively shot down the program, introducing new policies eliminating the curriculum from schools, despite its apparent success.

The Tucson schools controversy had nothing to do with security matters, Tirman observes. Instead it showed, he writes in the book, "the fissures in Arizona's political culture when it came to the sensitive issues immigration brought to the fore — race and ethnicity, language, jobs, education, and, at root, what it means to be an American."

It also indicates that a greater immigrant presence is accompanied by a greater backlash against those new residents; Arizona is now 30 percent Latino, but, as Tirman notes, has become "the leading anti-immigration-reform state," as well.

To be sure, Tirman allows, clashes over "culture" are often heightened by difficult economic circumstances; as middle-class wages have stagnated in recent decades, immigration has become more of a hot-button issue. In all, 45 states have passed immigration restrictions (on top of federal law) in the last two decades.

"I think there's no question that the resistance to immigration grows more voluble during times of economic stress," says Tirman, while noting that the current debate is "more contentious" than it was in the more rosy economic circumstances of the 1990s. More recently, he notes, "George W. Bush's reform package of 2006-2007 was shot down at a time when the economy was beginning to weaken. And the economy has been rocky ever since, so it's no surprise there's been opposition to the more recent reform efforts."

The Long March

Dream Chasers has received praise from other scholars. Derek Shearer, a professor of diplomacy at Occidental College, calls it "an essential primer that explains immigration in the context of American politics and the global economy."

Tirman, for his part, believes the future holds both wider tolerance of immigrants from Latin America among most U.S. citizens, but a continued resistance to loosening immigration law on the policy level.

Polling, he notes, shows that a majority of Americans seem amenable to reforms such as the ones both Bush and President Barack Obama have proposed, even as Congress prefers not to take action on the matter.

"The public has moved a long way in the last 20 or 30 years toward acceptance, and I think that's based on a kind of recognition that we've had all these people here, 11 million [undocumented immigrants], not really doing much harm," says Tirman, who himself favors a more open set of immigration laws.

At the same time, he notes, the generally sluggish global economy, particularly in Mexico and some part of Latin America, may only provide more impetus for people to migrate to the U.S. without documented status. And that heightened presence could also fortify resistance to immigration among the Americans already set against it.

"We are going to be having these issues for a long, long time," Tirman says, "so we had better understand their origins."

Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe visits MIT CIS

by Peter Dizikes, MIT News Office | Originally published here

Prime Minister Shinzo Abe

Prime Minister Shinzo Abe of Japan visited MIT as part of his weeklong trip to the U.S., participating in a roundtable discussion of innovation strategies during his stop at the Institute.

Abe called MIT a "center of innovation in the world" and said he was "very impressed and grateful" for the remarks on innovation at the meeting with MIT faculty in fields ranging from bioscience to management and political science.

Abe added that encouraging a "virtuous circle" of innovation, including academia, was "one of the pillars of my growth strategy," and emphasized his commitment to seeing women have an equal role in innovation and entrepreneurship. Japan will "double our efforts so that female leaders have a better chance," Abe said, asserting that he wants to "create a society where women can shine."

Abe also toured three research labs in the MIT Media Lab, and met with MIT President L. Rafael Reif, who in welcoming remarks noted the extensive ties between MIT and Japan.

"Japan is a country MIT has studied and admired for many years," Reif said, noting that 39 current courses at the Institute focus on Japan. Moreover, Reif observed, over 1,000 undergraduates have worked and studied in Japan as part of the MIT International Science and Technology Initiatives (MISTI) program, which places students in internships; today, more than 1,600 MIT alumni also live in Japan.

In conjunction with Abe's visit, the government of Japan announced a new gift to MIT.

The gift takes the form of a fund that will initially support research in Japanese politics and diplomacy at MIT's Center for International Studies (CIS) and, in its second phase, the creation of a new chaired professorship, to be titled the Professor of Modern and Contemporary Japanese Politics and Diplomacy, within MIT's Department of Political Science.

As the title of the chair suggests, the new position will focus on current-day issues in Japanese politics and international relations, building on MIT's existing strengths in those areas. The gift will take effect ahead of the start of the 2015-16 academic year.

Innovation from many perspectives

Abe began his visit by talking with researchers in the Media Lab, guided by Media Lab Director Joi Ito. Abe listened to research presentations by Neri Oxman, the Sony Corporation Career Development Associate Professor of Media Arts and Sciences and director of the Mediated Matter group, along with Chikara Inamura and John Klein, graduate students in the group; Hugh Herr, associate professor of media arts and sciences and head of the Biomechatronics group; and graduate student Philipp Schoessler, who works with Hiroshi Ishii, the Jerome B. Wiesner Professor and director of the Tangible Media group.

During the roundtable discussion on innovation, held on the sixth floor of the Media Lab, faculty members took turns making presentations before Abe responded to the group.

Political scientist Richard Samuels, the Ford International Professor and director of CIS, noted that MIT and Japan have historical ties dating to the 1870s, soon after Japan opened to the West; he added that Japan's "spirit of innovation and improvement has never flagged." Still, Samuels suggested, while Japan was viewed in the 1980s as the "model for how to do technology right," today's innovation landscape is more open-ended and depends on access to capital, a university-based research and spinoff culture, and more.

Other faculty discussed what they regard as especially crucial elements of an innovation ecosystem. Neuroscientist Susumu Tonegawa, the Picower Professor at MIT, recommended alterations in the rules of Japanese universities to allow professors more time pursuing off-campus research. He added that it is "important for the Japanese government to continue to support fundamental research."

Robert Langer, the David H. Koch Institute Professor at MIT, also emphasized the significance of academic research in innovation. He cited Cambridge's biotechnology sector as an example, saying growth "will follow [if we] fund universities to do the best research, and train the best students in the world."

Some of the MIT faculty present study innovation, and offered remarks on that topic. Suzanne Berger, the Raphael Dorman and Helen Starbuck Professor of International Relations at MIT, recommended that Japan pursue growth opportunities in advanced manufacturing and connected fields. "There is such a tight connection between innovation and production," Berger said.

Fiona Murray, the Bill Porter Professor of Entrepreneurship, associate dean for innovation in the MIT Sloan School of Management, and co-director of the MIT Innovation Initiative, added to Abe's remarks about gender and entrepreneurship, noting that "male and female graduates are equally interested in taking this path." She also observed that sound policies spark innovation, saying there are "important ways that governments have brought stakeholders together to effect change."

Kenneth Oye, an MIT political scientist with expertise in both Japan and in technological regulation, suggested that forward-looking attempts to gauge the risks of new technologies, particularly in biomedical research, were in the "common interest" of the U.S. and Japan. In turn, he said, "realizing the consequences" of evolving technologies would make it easier for widely useful new tools to get adopted.

For his part, Ito suggested that new tools and techniques have made sophisticated, interdisciplinary innovation more plausible at smaller scales, and suggested that it is important for funders to give researchers room to make discoveries—since many of them are tangential to the original aims of a research project.

"Japan really can build the same kind of economy we see here in Massachusetts," Ito suggested.

Abe: Japan backs a "similar model"

In response to these comments from the discussants, Abe said the interdisciplinary nature of the projects on display in the Media Lab created "quite an insightful moment" for him.

"We would like to see further fruition of a similar model," Abe added, referring to Japanese efforts to build an innovation ecosystem in the city of Okinawa, drawing upon contributions from academia, industry, and government.

Abe also praised Samuels, noting that the political scientist's scholarship had been "very effective" in "deepening relations between Japan and United States."

Abe's trip to the U.S. coincides with the 70th anniversary of the end of World War II, in which Japan and the U.S. were adversaries. Abe will meet at the White House with President Barack Obama, and on Wednesday will deliver the first address by a Japanese leader to a joint session of Congress.

The Japanese prime minister will also discuss global economic and diplomatic issues while in Washington, including the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a potential trade agreement that has drawn some domestic opposition in both the U.S. and Japan. Abe will make stops in Los Angeles and San Francisco later in the week before returning to Japan.

3 Questions: Kenneth Oye on Regulating Drugs

by Peter Dizikes, MIT News Office | Originally published here

Kenneth Oye

Writing in the journal Nature Chemical Biology, researchers at the University of California at Berkeley have announced a new method that could make it easier to produce drugs such as morphine. The publication has focused attention on the eventual possibility that such substances could be manufactured illicitly in small-scale labs. Political scientists Kenneth Oye and Chappell Lawson of MIT, along with Tania Bubela of Concordia University in Montreal, authored an accompanying commentary about the regulatory issues involved. Oye answered questions on the subject for MIT News.

Q. What is this significant new advance?

A. All of the steps needed to create a pathway in yeast capable of producing morphine from glucose have now been realized. Specifically, on May 18, the Dueber lab at the University of California at Berkeley published an article in Nature Chemical Biology on a pathway from glucose through norcoclaurine / norlaudanosoline to (S)-reticuline. The Faccini lab at the University of Calgary has worked on epimerization of (S)-reticuline to (R)-reticuline. Last month, the Martin lab at Concordia University published an article in PLoS One on a pathway from (R)-reticuline through thebaine to morphine. Independently of these efforts, the Smolke lab at Stanford University has been developing yeast-based pathways for opiate production for over eight years.

In short, an integrated glucose-to-morphine pathway in yeast is now feasible, with substantial potential benefits. Drug developers are testing novel analgesics that may be safer and less addictive than traditional opiates. Because yeast-based opiate-production pathways may be altered more easily than pathways in opium poppy, the work of these groups may prove useful in the production of these next-generation analgesics.

Q. Why should it be regulated?

A. The development of yeast-based opiate-production platforms presents significant challenges to public health and safety. Opiates now reach illicit markets through two principal channels: First, legal prescriptions for oxycodone, hydrocodone, and other opiates are commonly diverted to unauthorized use. Second, illicitly cultivated opium poppies in Afghanistan, Myanmar, Laos, Mexico, and other countries are processed into heroin, and distributed by criminal networks.

Yeast-based opiate synthesis could create a third pathway of decentralized, small-scale production. Because yeast is easy to conceal, grow, and transport, law enforcement and criminal syndicates would both have difficulty controlling dissemination of an opiate-producing yeast strain. The essentials of yeast cultivation are well understood by home brewers, and fermentation equipment is inexpensive and widely available.

Access to low-cost opiates would increase opiate use and abuse. The legal sale of tincture of opium in the late 19th and early 20th century led to widespread addiction. Likewise, rates of addiction to prescription opiates surged when new painkillers became more widely available and fell somewhat when additional restrictions were imposed. More generally, increased access to other addictive substances, such as methamphetamine, has been associated with increased use. Yeast-based production of opiates would thus be likely to increase the number of opiate users and addicts.

Q. Which regulatory principles, or policy specifics, are most suited to this case?

A. As they were submitting their articles to journals, the Dueber and Martin labs asked Tania Bubela of Concordia University, Chappell Lawson of MIT, and me to develop recommendations on how to address risks associated with their opiate-synthesis work. Our policy recommendations are designed to allow potentially beneficial research while limiting the likelihood of unintentional release of an opiate-producing yeast strain. We offer four basic recommendations and a fifth observation.

First, we recommend adjustments in the design of yeast strains to limit illicit appeal. These measures included producing end-products with less appeal for illicit use, making yeast strains harder to cultivate, and creating markers to enable easy detection of opiate-producing strains. Second, we recommend basic lab security measures and personnel checks to limit the likelihood of theft or sale of opiate-producing strains from academic labs. Third, we recommend measures to make it harder for criminal organizations to engineer yeast strains … by asking gene-synthesis consortiums and firms to screen orders by adding opiate-producing, nonpathogenic yeast strains to current blacklists of pathogens. Fourth, we recommend changes in domestic regulations, including licensing of opiate-producing yeast strains and activation of international consultation mechanisms in the International Narcotics Control Board and the International Expert Group on Biosecurity and Biosafety Regulation.

Finally, the case of opiate synthesis in yeast should be viewed in light of two broader trends. One is that the field of biological engineering is now moving very quickly. New tools like CRISPR, used for gene editing, are more efficient, and inventories of biological parts suitable for repurposing are now useful in a practical way. Results that were once an abstract possibility are being realized — gene drives, human germline modification, and opiate synthesis are examples.

Another is that technologists developing these powerful applications are now stepping forward early to encourage discussion of benefits and risks before, rather than after, the fact — early enough to conduct research to address areas of uncertainty, early enough to identify gaps in domestic regulations and international conventions, and early enough to have a deliberate and informed discussion of risks. Prominent scientists have stepped forward early in the case of opiate synthesis, gene drives, and human germline modification. Furthermore, the National Science Foundation, the Sloan Foundation, and other funders have provided support for precisely this sort of responsible engagement.

The particulars of the opiate synthesis case are significant. But these two more general trends are the important larger story.