Meet MIT's experts in Asian security

SHASS Communications

First published here.

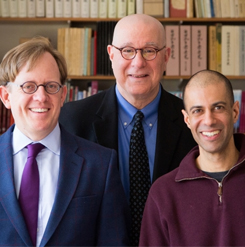

MIT Asian security studies faculty (left to right) M. Taylor Fravel, Richard Samuels, and Vipin Narang train the next generation of scholars and security policy analysts; counsel national security officials in the U.S. and abroad; and inform policy through publications and frequent contributions to public debates.

Photo courtesy Jon Sachs/SHASS Communications

These are fraught times for scholars of security studies, perhaps even more so for those engaged with Asia. Just as the 20th century was proclaimed “the American century,” many observers today speak of the 21st century as “the Asian century.” Yet the Asian strategic landscape holds many potential dangers including nationalist rivalries, changes in the distribution of power, and proliferation of weapons of mass destruction (WMD). “It’s a moment when our ideas, training, and teaching seem more relevant than ever,” says Vipin Narang, the Mitsui Career Development Associate Professor of Political Science. “Given the uncertainties of the Trump administration’s foreign policy priorities, certain bedrock principles of American foreign policy that we thought were settled might not be, including a commitment to nuclear nonproliferation and US alliances.”

Narang, who specializes in South Asian security and nuclear security, is one of three principal faculty members with MIT’s Security Studies Program who focus on Asia. He works alongside Richard Samuels, the Ford International Professor of Political Science and director of the Center for International Studies, a specialist in Japanese national security; and M. Taylor Fravel, associate professor of political science, who studies Chinese foreign and security policies.

Described broadly, the core mission of the trio “is to understand how the states in the region conceive their grand strategies and military postures,” says Samuels. In pursuit of this goal, the Asian security faculty train the next generation of scholars and security policy analysts; counsel national security officials in the United States and abroad; and inform policy, by publishing books and articles in scholarly and accessible journals and websites, frequently contributing to public debates on timely issues.

SHASS Communications had a conversation recently with Narang, Fravel, and Samuels about emerging security challenges in their domain, and opportunities for responding as scholars, public commentators, and teachers.

What hot spots should foreign policy makers, and the rest of us, be focused on?

Samuels: There are three: China, China, and China. The balance of power in the region is shifting in China’s favor, and its rise and the measures it takes to provide for its security fashion the kinds of responses Japan and India—and the United States—make.

Narang: You can’t afford a trade war or a shooting war with China.

Fravel: The kind of great power competition you saw playing out in Europe in the 20th century is now starting to happen in Asia. So if you’re worried about the potentially devastating effects such competition can have, when the world’s greatest powers contend with each other and it gets violent, it’s much more likely to happen in Asia today than in other parts of the world.

Narang: It’s not just academic. There are active and ongoing conflicts with deep historical roots between China and Japan, South Korea and China and Japan, India and Pakistan, and you have an alley of nuclear weapons from Pakistan out to North Korea, which may expand.

Samuels: And a Japan and South Korea that could turn in that direction quite quickly.

What specific issues are of concern to you in your respective regions?

Fravel: There are territorial conflicts in the South China and East China seas that have been escalating to high levels of tension. These conflicts variously involve China and Japan in the East China Sea and Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia, Brunei, and Taiwan in the South China Sea. Each time one nation takes action to enhance its control of disputed land or adjacent waters, another state responds in a similar way that creates a vicious cycle. This matters to the United States because these conflicts involve US allies, such as Japan or the Philippines, whom the United States is obligated to defend.

Samuels: Despite US security guarantees, the Japanese feel insecure and vulnerable. They have highly capable naval and air forces, but their military doctrine has required them to commit to only the minimum use of force. That commitment is being strained by China’s rise and North Korean provocations, which is forcing a rethinking of Japan’s military posture. Prime Minister Abe visited the newly elected President Trump twice seeking reassurance on US security commitments.

Narang: South Asia is an unfortunate test bed for how new nuclear powers behave. The conflict between India and Pakistan is heating up right now, just as both are expanding their nuclear weapons arsenals. The big change involves attacks across what both countries define as the Line of Control, a fenced off position in Kashmir which the other side’s forces rarely cross. But both sides have attacked across this line in recent months, in one case burning over a dozen Indian soldiers alive, another involving beheadings and holding soldiers’ families hostage India’s government has begun removing the restraints on retaliation, publicly crossing the Line of Control in response for the first time in over a decade. If the Pakistani attacks increase in intensity, India may not restrict its retaliation to the Line of Control. The US needs to understand these tinderboxes, and figure out how to craft incentives for Pakistan to stop supporting militancy as a strategic asset of the state and how to address growing nuclear risks between the two nations

Samuels: And North Korea never goes away. Like a villain from central casting, it always seems poised to do the wrong thing—for its ally in Beijing, its neighbors in South Korea and Japan, and most of all, for itself.

Narang: China fears a collapse of North Korea and the threat of refugees more than it fears its nuclear weapons. This problem can’t be solved unless the U.S. and China agree on a playbook.

How do you see your role in helping keep the peace, or at least bringing understanding to issues in a way that doesn’t contribute to the volatility?

Fravel: I participate in several regular dialogues with US and Chinese experts, which try to develop recommendations for our respective governments. I also speak regularly with Western media to help them understand the stakes and dynamics in these disputes and am active on Twitter. Beyond my public engagement, I’m working on a project that explores ways to defuse tensions in the region’s territorial and maritime boundary disputes. For instance, the South China Sea is the perhaps most overfished fishery in the world, and fisheries competition elevates the importance of maritime claims. A joint fishing or environmental protection agreement among the claimants could lower the importance of claims to the islands and adjacent waters and thereby decrease tensions and the potential for conflict. I’m also finishing a book tracing the evolution of China’s military strategy since 1949, from being defensively oriented to acquiring increasingly potent offensive capability. Spinoffs of this research might offer policymakers a framework for assessing how China’s military strategy may change in the future.

Narang: I have regularly written on the India’s nuclear doctrine in its leading English language newspapers. I recently published a longer-form piece on how surgical strikes across the Line of Control could lead to a larger conventional war between India and Pakistan. Also, with my colleagues, I participate in government-sponsored exercises and dialogues intended to remind their national security establishments what’s at stake in these conflicts. As subject matter experts, we provide specific assessments and reality checks in the scenarios, and they get to see the results of their decisions and just how quickly things can spiral out of control.

Samuels: We are all engaged in public discourse and are committed to trying to improve it. For instance, I have worked with the Aspen Institute to connect members of Congress with their Japanese and Korean counterparts. My colleagues and I have briefed the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the MIT Center for International Studies runs an annual program, Seminar XXI, for mid-career military, intelligence and NGO officials, which draws heavily on SSP [Security Studies Program] faculty and has had enormous impact. There is a competition among Pentagon employees and service branches for joining the seminar—usually at the level equivalent to Lt. Colonel in the Army. Many become flag officers, and a disproportionate number have become chiefs of staff. I spend as much time talking to Japanese media and government officials as I do to the American media and officials. When they seek me out, it’s for help to interpret US. policy, and when I seek them out it’s to understand Japan’s. Two years ago, the Japan Ministry of Foreign Affairs gave us a $5 million gift to endowment to support our research on Japanese politics and diplomacy. This is helping fund our graduate students, a principal research scientist who focuses on the Asian military balance, and my own project on the history of the Japanese intelligence community.

What part does teaching play in your mission?

Narang: Our graduate students are grounded in political science as a discipline, and engaged with contemporary issues and problems. MIT is one of the few places where young scholars are actively encouraged to engage with the policy community.

Fravel: This is distinctively MIT. Many political science departments shun direct engagement with policy makers or downplay applied research. And there’s not another academic department or research center at a major research university that has in one place expertise on security issues involving China, Japan, and India—the major powers in the region. So if you’re interested in any one of these countries, or their interactions with each other and the rest of the world, MIT is an attractive place to be a graduate student.

Samuels: We take our role of being public intellectuals very seriously, so this means that all of us, including graduate students, publish regularly in accessible journals, such as Foreign Affairs, The National Interest, and policy-relevant blogs, in addition to producing more scholarly work. Our current graduate students, almost all of whom are women, are publishing on topics from Chinese nuclear, space, and cyber strategies, to US-Japan alliance politics. And one graduate of our program, Eric Heginbotham, has returned to MIT from the RAND Corporation, and is publishing influential articles on Chinese and Japanese military and intelligence issues.

Do you have any final thoughts about your work at the start of this new political era in the US?

Narang: Early in presidencies is when foreign actors and adversaries tend to test administrations to see how they will react. Our role as policy-engaged academics is to frame debates, provide information based on areas of expertise and insights to help avoid mistakes. That’s what I hope we can do.

Fravel: The greatest challenge for all of us is uncertainty, and what might happen if a crisis or incident occurs in the region that engages US interests and demands a response. The Asia policy (and broader foreign policies) of the Trump administration remain uncertain and could go in several different directions. At the same time, China will be selecting a new Politburo Standing Committee this fall. South Korea will soon have a new president. It’s more important than ever to be engaged publicly on the security issues in Asia, to help the public understand the issues at stake for states in the region and for the United States.

Samuels: We’re here to help.

Jeanne Guillemin on the recent chemical attack in Syria

Michelle Nhuch

First published here.

Jeanne Guillemin

Photo courtesy Jean-Baptiste Guillemin

On April 4, a suspected nerve gas attack killed at least 80 in Khan Sheikhun, in Syria’s Idlib Province. Nikki Haley, the US Ambassador to the United Nations and the current UN Security Council president, stated shortly after the incident that members "are hoping to get as much information” as they can about the event.

Jeanne Guillemin, a medical anthropologist and a senior fellow in the MIT Security Studies Program, recently answered a few questions on the attack. Guillemin is an authority on biological weapons and has published four books on the topic. Her latest, "Hidden Atrocities: Japanese Germ Warfare and American Obstruction of Justice at the Tokyo Trial," will be published by Columbia University Press in September.

What do we now know about the attack?

JG: The process of investigation will be difficult, given the ongoing war and secrecy on the part of Syria and others. It seems certain that the regime of Syria’s President al-Assad or some element thereof not only violated treaty obligations regarding chemical weapons but could be complicit in a major war crime.

On a technical level, the chemical agent that caused more than 80 deaths and many injuries has been identified by the United Kingdom as sarin, which accords with medical records. The timing of the attack was April 4 at just before 7 AM local time, optimal for dispersal. Much less or nothing is reliably known regarding the munition and its source.

The Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), the operational arm of the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) in The Hague, is the lead agency for investigating the nerve gas attack. The OPCW can count on assistance from the United Nations Joint Investigative Mechanism (JIM), created by the Security Council with all permanent members in agreement. OPCW investigations are kept secret until the final reports are released, which can take months, and their mandate does not extend to identifying perpetrators. The mandate of the JIM is broader and does extend to estimating perpetrators, which makes its eventual report important.

Based on your expertise on the historical use of chemical weapons, why would Assad strike now? Is he likely to strike again?

JG: The use of chemical weapons in war, starting in April 1915 with the German release of chlorine gas on Allied trenches at Ypres, has invariably been to break an impasse by targeting a defenseless enemy, those lacking protection such as gas masks or antidotes. For Syria, frustration with rebel holdouts in Idlib Province may have provoked the attack; one wonders, though, exactly what authorities reasoned that killing civilians with nerve gas could be carried out without controversy—and without jeopardizing the new potential for cooperation with the Trump administration.

The political furor created by the social media images of the victims make it unlikely that President al-Assad, if he ordered or permitted the attacks, would venture any more. For years, though, Syria has been getting a pass from the international community regarding its less-than-complete compliance with the CWC, to which it acceded in October 2013. In 2014, the belief that Syria’s declaration of its chemical weapons contained gaps and inconsistencies prompted the Director-General of the OPCW to send a special team of technical investigators on 18 trips to Syria to do what proved impossible: to verify that Syria’s declaration was in accordance with the CWC. The UN Security Council was fully advised of OPCW reports, but no action was taken to bring Syria in line.

Currently the Russian government is taking al-Assad's protestations of innocence at face value. At the same time, though, Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov has spoken strongly in favor of UN investigations and asserted that Syria will be forthcoming about its military activities in the region at the time of the April 4 sarin attack. If evidence points clearly to al-Assad’s forces, which the US government has already publicly blamed, Putin will have to address the difficult problem of regime change in Syria—or risk his own legitimacy by supporting a Syrian president many feel is at best a loose cannon and at worst the murderer of his own people.

What are psychological and physical effects of this kind of attack, and how does one determine who was responsible?

JG: Follow-up information from the 1988 chemical attack in Halabja, Iraq, and the 2013 chemical attack in Ghouta, Syria, illustrates the terrifying impact of aerial chemical attacks on defenseless populations already under siege.

In Halabja, the attacks with blistering mustard and with sarin, combined with conventional bombings, were part of Saddam Hussein’s punitive objective to eliminate the Kurds from Iraq.

The unusual strikes on Ghouta and Khan Sheikhun seem more intended to terrify Syrian civilians, that is, to frighten survivors and witnesses (even those watching on the internet) into submission to the enemy aggressor, whose power to rapidly asphyxiate hundreds must seem mythic, especially when done with impunity, without legal repercussions.

Over time, the criminal responsibility for the April 4 sarin attack might be put on Syrian officials, who may well be prosecuted at the International Criminal Court (ICC). The court’s statute contains language banning the use of poisons taken directly from the Geneva Protocol; the prosecution of murderous attacks on defenseless populations is, of course, central to the ICC mission, regardless of means. The broader responsibility for what has happened in Syria and for the extreme vulnerability of its civilian population throughout the war lies with the international community. This week, one hears the Chinese delegate to the United Nations calling for a political solution, rather than a military showdown between the United States and Russia. After this latest barbarism, is it too much to ask for international safe zones and a cease fire?

Building connections between the Institute and countries in the Arab world

Caroline Knox

First published here.

In 2016, The MIT-Arab World Program matched 19 MIT students with teaching and internship placements in Jordan, home of the archaeological city of Petra.

Photo: Kobey Mortenson/Flickr

Launched in 2014, the MIT-Arab World Program—a part of MIT International Science and Technology Initiatives (MISTI)—was created in an effort to strengthen ties between MIT and countries of the Arab World. Through student projects and faculty collaborations, the program offers opportunities for immersive and meaningful interaction in the region with the aim to empower participants to be bridges between MIT, the United States and the Arab World.

“At this pivotal time in the Middle East, the MIT-Arab World Program seeks to build critical scientific and cultural connections between MIT and the Arabic-speaking world,” says Philip Khoury, MIT Associate Provost, Ford International Professor of History, and the MIT-Arab World faculty director. Like his fellow MISTI faculty directors, Khoury sets the strategic path for the program in collaboration with the program’s managing director.

Student activities

MIT-Arab World’s main activity is a 12-week student internship program for MIT undergrads and graduate students looking to experience the workplace in companies and universities in the Arab World. Over the past two years, 14 MIT students have been matched with professional internships in Jordan and Morocco. Building on their course of study, students worked with small startups, non-governmental organizations, and global companies rooted in the Arab World including Turath, Petra Engineering, Curlstone, Tamatem, OCP, and the University Hassan II of Casablanca.

Like all MISTI internship programs, MIT-Arab World strives to help its students develop intercultural skills through hands-on experience working alongside international colleagues. “I was relieved to discover that I could indeed cross the boundaries of language and culture to do good work with others,” shares MIT-Arab World intern Elisa Young, a senior in electrical engineering and computer science. At Jordanian host companies Curl Stone Entertainment, an animation studio that creates stories and heroes for young audiences in the Arab-speaking world, and Tatamen, a mobile gaming startup that produces games and apps for the MENA region, Young was immersed in distinctively Middle Eastern animation and gaming. “I felt like the Middle East gets little media and entertainment coverage that is not related to conflicts in the region,” Young says. “I wanted to more deeply understand their culture and learn about the reality of the people by living in their midst. During her time in Amman, Young not only learned to navigate a new culture and society in everyday life, but she also learned to incorporate cultural aspects — such as specific fonts, colors, and gameplay elements better suited to tastes in the region — in her work.

In addition to the internship program, MIT-Arab World offers teaching opportunities to MIT students through MISTI’s Global Teaching Labs (GTL) program. For 3-4 weeks over MIT’s Independent Activities Period in January, students teach STEM and entrepreneurship courses to high school students in Arab states. In 2016, the first cohort of 11 students traveled to Jordan, where they broke into three teams to teach STEM, entrepreneurship, and 3-D printing at King’s Academy in Madaba, Jubilee School in Amman, and the 3Dmena Maker Space in Amman. “I was teaching but I was also learning at the same time,” explains Evan Denmark, a senior in electrical engineering and computer science who taught physics to a 9th grade class at King’s Academy. “I had to learn how to engage my students and better understand how they learned most effectively.”

In January, another 17 students taught high school students and Syrian refugees in Jordan and Morocco through GTL. Excited for a chance to return to the region, Denmark traveled to Jordan this with this group to film peer MIT students teaching in the field. “Being a photographer and videographer, I wanted to make my own documentary about this region and MIT’s educational initiatives here,” he says. “Because of my own GTL experience, I had the confidence to explore my opportunities; to take my own project and technical skills I learned at MIT and then bring them to places across the world.”

As part of the MISTI program, MIT-Arab World interns and GTL students are required to participate in a series of cultural training modules covering topics such as cross-cultural communication, current events, technology, and innovation in the host country. These sessions, combined with MIT coursework, ensure that students have a rich experience that broadens their academic, professional, and personal horizons and prepares them to be global leaders in their field of study.

Faculty funds

The MISTI Global Seed Funds (GSF), which support early-stage collaborations between MIT researchers and their counterparts around the globe, has supported faculty projects in the Arab world since 2014. Encouraged to include MIT students in their projects, MIT faculty grantees use the funds to meet and work with their international peers with the aim of developing and launching joint research projects.

The award allows the project to move forward as it gives the opportunity for the members of the two teams to meet and work together hand-by-hand and get to exchange their expertise,” explains MIT-Egypt Seed Fund grantee and MIT Professor Vladamir Bulović, associate dean for innovation in the MIT School of Engineering, MacVicar Fellow, and the Fariborz Maseeh (1990) Chair in Emerging Technology. Working in collaboration with Nageh Allam, assistant professor at the American University in Cairo, Bulović set out to construct high performance, affordable, and air-stable inorganic photoelectrochemical devices to enable long-term, scalable solar energy conversion and storage. “Our two teams shared their ideas about their work experience, and how they can mix their fabrication techniques in one single device. This cooperation revealed the capability to mix both techniques to build one single device based on the experience of the two teams to enhance the performance of the solar cell devices.”

Over the past three years, faculty from the Arab world and MIT faculty have received eight grants to work in Egypt and Jordan. Project topics include design modifications to refugee camps; water and energy; and health. The MISTI GSF 2016-2017 cycle has ended, but the 2017-18 call for proposals will launch this May.

MIT-Arab world

This past year 24 students and five faculty collaborated closely with their counterparts through the MIT-Arab World Program. Going forward, the program’s leaders plan to develop more opportunities for MIT students to engage with the region, offer more faculty funds for collaboration in the region as a whole, promote the study of Arabic and strengthen the region-specific educational training.

MISTI is a part of the Center for International Studies, a program at the School of Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences (SHASS).

CIS Starr Forum: Brexit, Europe, & Trump

Philip Martin

Jack Straw, Former British Foreign Secretary

What do the recent tides of populist sentiment in the UK and the US—culminating in the exit of Britain from the European Union and the election of Donald Trump to the US Presidency—imply for Europe’s political future? How did these two great powers arrive at this political moment? On Thursday, April 6th, John Whitaker “Jack” Straw, a Member of Parliament for Blackburn from 1979 to 2015 and the former Home Secretary and Foreign Secretary in the UK’s Labour government, offered a wide-ranging perspective on these questions. Straw outlined the differences and similarities between the contemporary political climates in the US and the UK, and speculated on what these developments might entail for the prospects of a unified Europe.

The origins of Brexit

Straw began by arguing that one cannot understand the choice of the UK to leave the European Union in 2016 without appreciating the history of Britain’s position vis-a-vis European integration in the 20th century. The idea of “shared sovereignty” was highly contested in Britain in the 1950s and 1960s, Straw reminded the audience, and many feared that UK membership in a unified Europe would effectively mean “the end of Britain as an independent state.” Straw admitted that he himself had initially opposed the European common market in the 1970s out of the fear that it could lead to an unwieldly political “superstructure”. This pronounced fear of a loss of British sovereignty persisted, and ultimately culminated in the 2016 referendum result.

Straw also noted the important changes in domestic sentiments within the UK over time, notably the positions of its smaller nations such as Scotland and Northern Ireland. While these nations were strongly “Euro-skeptical” in the 1980s when the UK voted to join the EU, they were among the staunchest supporters for “Remain” in 2016.

Brexit and Trump: similarities and differences

Although the Brexit referendum and US election differed in important ways, Straw noted a number of similarities between them. First, both the “Leave” and Trump campaigns often appealed to the “heart” of voters rather than their “head,” relying on emotional sentiments designed to inspire strong reactions of fear and anger. These scare tactics often relied on dubious facts, such as the rumour purveyed by the “Leave” campaign that Turkey was soon to join the EU, as well as misleading figures about the financial savings to Britain of leaving the EU. Added to this cauldron of fear was the perception, reinforced by the “Leave” campaign, that Europe had lost control of its borders and that the UK would soon be overrun by “the other.”

Straw argued that these tactics—which draw parallels to Trump campaign themes—left the “Stay” campaign in the difficult situation of continually reacting to the emotional appeals of their opponents. Moreover, unlike in a regular election among political parties, voters in the Brexit referendum often had little information to anchor their prior opinions, making rumours and exaggerated claims an especially potent tool of persuasion.

Straw also noted similarities in the voting bases for “Leave” and Trump. Both drew their strongest support in rural areas, and both skewed towards older voters. UK voters with lower incomes were more likely to vote Leave, although wealthier business owners who felt alienated by the country’s metropolitan elite and the unchecked expansion of European political integration also supported the Leave campaign. Straw emphasized that it was above all the sense of growing voter marginalization from the centers of political power, a fear shared Trump campaign supporters, that inspired the strongest motivation for Leave voters.

However, Straw noted important differences between domestic politics of the UK and the US as well. First, the Brexit referendum was not a regular political election but a one-off decision that would permanently alter the country’s relationship to Europe. Trump’s electoral victory, meanwhile, falls within the “normal” constitutional order of the US and thus is confined by institutional checks-and-balances. Second, the Leave campaign garnered a clear majority of the popular vote, whereas Trump did not. Finally, Straw noted, the UK and US differ deeply in their domestic democratic institutions, particularly concerning the ability of politicians to influence redistricting decisions and the role of corporate financing in political campaigns.

Effects on the wider world?

Straw finally considered the impacts of Brexit and Trump for other states in Europe. Among the states most likely to be impacted is Germany. Germany, Straw observed, will now assume an unwanted position of dominance within the EU, while simultaneously losing an ideological ally on the European Council. This shift may inspire greater dissatisfaction on the part of other EU member-states, further straining European integration.

Moreover, the European economic market is likely to experience even greater stress in its effort to juggle its diverse component economies within a single monetary union. Europe’s supranational political institutions, Straw argued, are poorly positioned to handle these challenges in a transparent and democratic fashion. The resulting state of uncertainty in Europe could open further avenues for influence and manipulation by other powers such as Russia and the United States.

However, Straw also stressed the resiliency and adaptability of both the UK and Europe. The dire predictions of economic collapse after Brexit have not yet materialized, and geographic realities ensure that Europe will continue to be an important trading partner with the UK for the foreseeable future. Britain’s intelligence and security capabilities remain unparalleled on the continent, which will ensure the continued influence of the UK in other domains. Finally, the UK and Europe remain ideologically aligned on major foreign issues such as climate change and the Middle East. Thus, the UK is likely to continue to engage extensively with Europe despite the (disappointing for Straw) results of Brexit.

In the Q-and-A from the audience, Straw addressed several additional foreign policy questions raised by Brexit and Trump. These included the resiliency of the US-UK alliance, the role of China in the new Europe, the rise of information manipulation and misinformation in politics, and the US-Russia relationship in the age of Trump.