This article first appeared on the New York Times here.

Multinational and nongovernmental aid organizations are sounding the alarm about a potential increase in cases of sexual exploitation, human trafficking and child abuse, as the number of vulnerable people fleeing the war in Ukraine continues to rise.

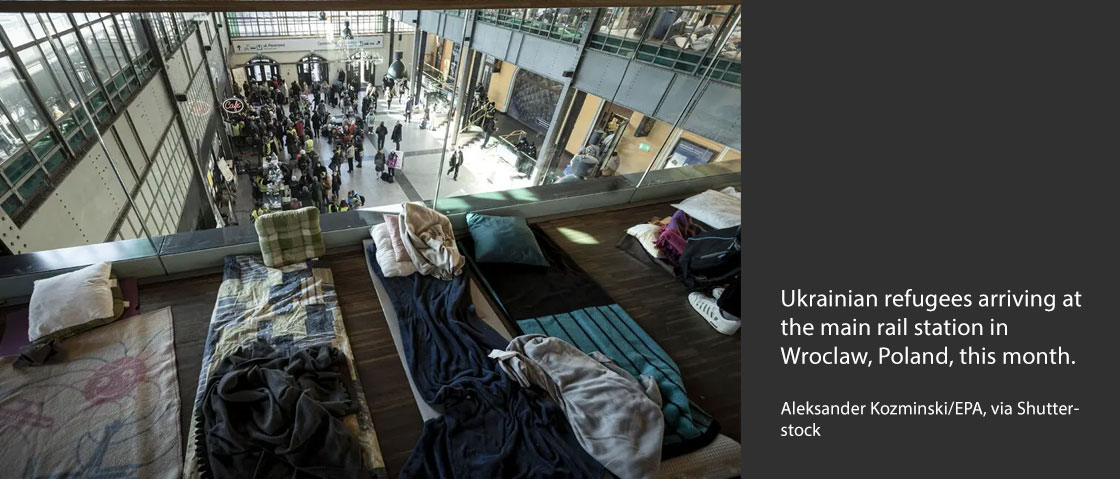

Of the more than 3 million Ukrainian refugees, the majority are women, children and older people, some of whom are unaccompanied and separated from family and friends.

“These groups can be especially vulnerable to the risk of trafficking as they leave their homes unexpectedly and might have their usual family networks and financial security seriously disrupted,” António Vitorino, the director general of the International Organization for Migration said on Wednesday.

Cases of sexual violence and attempts at trafficking have already been reported in the countries neighboring Ukraine, which have taken in the largest number of refugees.

Last week, the police in Wroclaw, Poland, arrested a 49-year-old Polish man on charges of raping a 19-year-old woman from Ukraine who was fleeing the war. According to the police, the man offered the woman shelter through one of many online websites connecting private Polish hosts with Ukrainian refugees.

“She had just escaped from war-torn Ukraine, did not speak Polish, did not know the city and had, in fact, never been to Poland. She had trusted a person who promised to help her,” the police said on Thursday.

More than 1.9 million Ukrainians have found asylum in Poland since the onset of the war three weeks ago. The unprecedented pace and scale gave rise to a grass-roots movement across Polish society, with hundreds of thousands of private individuals offering free shelter and transport to the refugees.

“The vast majority of people who are willing to help have good intentions, but unfortunately there are also those who want to take advantage of this situation,” the mayor of Warsaw, Rafał Trzaskowski, said during a recent news conference.

Homo Faber, a Polish organization working with refugees, has received reports from volunteers about suspicious looking people approaching young Ukrainian women at the border, at reception points or at train stations, offering them work with accommodation on the premises and refusing to register as official hosts.

“Unfortunately, human trafficking, sexual violence, child abuse and forced labor are byproducts of most conflicts,” Anna Dąbrowska from Homo Faber said.

So far, reports are isolated. But, aid organizations say, instances of violence and trafficking are less likely to be reported immediately after a mass displacement.

“It is unrealistic to expect refugees to report such cases as soon as they happen,” said Karolina Domagalska, of Feminoteka, a group that works with survivors of sexual violence. “We know from research that survivors often need time to tell their stories, and on top of that, these people are running away from war, so reporting may not be their first concern.”

A group of 42 Polish aid organizations published a joint appeal last week, calling on authorities to adopt coordinated, systemic measures to assure the safety of refugees. These include creating an official register of hosts and drivers to enable appropriate oversight, providing verified and safe information to the refugees, and creating safe spaces where they can report potential problems.

At the moment, the bulk of aid provided to the refugees rests on the shoulders of volunteers.

“The fact that people are inviting others under their roofs is impressive and heartwarming, but on the other hand, this movement is unregulated and lacks transparency, and, as such, it creates space for abuse,” said Joanna Garnier from La Strada foundation, a nongovernmental group based in Europe and dedicated to fighting human trafficking.