Elizabeth A Wood is Professor of Russian and Soviet History at MIT, where she also directs the Russian Studies Program and the MIT Russia and Eurasia Program. This blog post first appeared here.

On February 22, as the Ukraine crisis was unfolding and Russia was just hours away from invading its neighbor, Putin’s former Minister of Culture, Vladimir Medinsky, told journalists that Ukraine today has to be seen as “a historical phantom.” Putin, he said, is taking “historic” decisions in line with “the spirit of the times.” Five days later, Putin named Medinsky his chief negotiator for the Ukraine conflict. If we want to understand whether Putin has any commitment to these talks, we have to understand the view of both men (and many others) that Ukraine is not now nor should ever be an independent state. And we have to wonder what it means that the man placed in charge of the negotiations from the Russian side has explicitly called the country he is negotiating with a “phantom.”

Putin’s best biographers Fiona Hill and Clifford Gaddy, have famously referred to Mr Putin as “the History Man.” Perhaps, however, a better term would “the mythic man,” or the man who tries to make history. In the current war against Ukraine – which has to be seen as also a war against Belarus and against Russia itself – Putin has chosen to surround himself with an extremely small group of military hardliners in his decision-making, but he also relies heavily on his myth makers. In fact, the two are not entirely separate. Sergei Shoygu (Minister of Defense and close friend of Putin’s) and Sergey Naryshkin (head of the Foreign Intelligence Service, the SVR) both head historical societies. As Russian analysts Andrei Soldatov and Irina Borogan recently pointed out, these are “Putin’s history helpers”; they are the ones who create the ideological justifications for the invasion of Ukraine.

But one figure has gone unnoticed in the media and even by scholars: Vladimir Medinsky. And he is heading the negotiations. In terms of biography, Medinsky was himself born in central Ukraine in 1970, but left for Moscow in 1987 to study at the prestigious Moscow State Institute of International Relations (MGIMO). His patronymic “Rostislavovich” (son of Rostislav) means that whenever anyone addresses him by his formal names, he is reminded of two early princes of Kievan Rus (Rostislav Vsevolodvich, half brother of Vladimir Monomakh, and Rostislav Mstislavich, Prince of Smolensk, Novgorod and briefly of Kyiv itself). The name also means “to increase glory.”

How Medinsky views the Russian past

Looking at Medinsky’s writings – which frankly are extremely hard to read for a serious historian (they make me almost break out in hives), we can also see why Russia may have invaded Ukraine when it did. Journalists and scholarly analysts alike have tended to assume that the timing happened when it did because Putin et al share a perception of Western weakness and division, a conviction that US President Biden would respond only weakly because of his professed commitment to reconciliation and bringing allies together. I myself have written that Putin seems initially to have been trying to follow the playbook of his other wars: quick, decisive engagement with maximum force for a rapid victory that can be claimed as bloodless and doesn’t give enough time for outside responses. But the timing may also have to do with Medinsky’s and others’ sense of historical time.

On February 4 (2022), the semi-official website Istoriia.RF (History of Russia) published an article by Medinsky entitled “300 Years of the Russian Empire.” In that piece he reminds his readers that 2021 marked the 300th anniversary of the Russian Empire (named such after the Treaty of Nystadt and Peter the Great’s victory over the Swedes in 1721) with 2022 marking the 100th anniversary of the Soviet Empire when the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) was officially declared to be the successor state to the Russian Empire. By this logic, it makes sense for Russia to re-take Ukraine in 2022 as the heir to its previous empires. Medinsky opens his article by claiming that the Latin word “Imperium” (which is at the root of both “empire” and “imperious” in English) means “power” (vlast’ in Russian). “Empire,” he says should not be viewed in a negative light. It merely means the governmental form of different peoples living together “in a territory that objectively requires communicative, economic, – and sometimes military unity.”

Two weeks later (February 22), after Putin had “recognized” the breakaway republics of Donetsk and Luhansk as “independent,” Medinsky told Russian journalists that Ukraine today is merely a “historical phantom.” He references Putin as acting in the spirit of the times (literally, in the breathing of history, po dykhaniiu istorii). In this Hegelian spirit, he imagines that Putin is doing something inevitable, something that will be recognized by history as hugely significant, as in fact of “historical” importance. He justifies this by arguing that Ukraine is somehow fabricated (literally cut together of different pieces of fabric, skroennyi). A good lackey, he repeats Putin’s refrain from the previous summer that Ukraine is indivisible from the Russian Empire.

The Chain of Command for Rewriting History

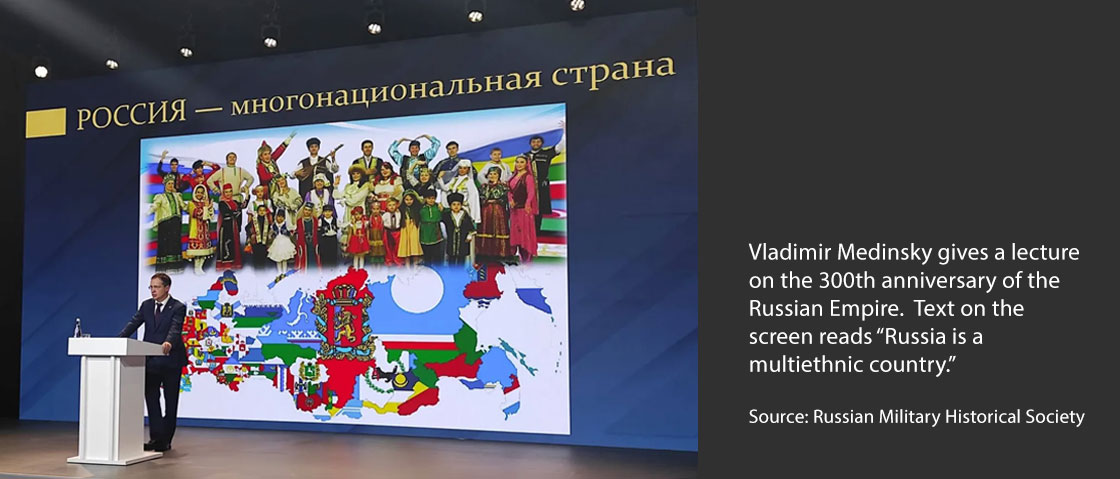

The chain of command for history production in Russia also tells us a lot. Medinsky himself has had a meteoric rise. He achieved the highest educational level in Russia [doktorat] in December 2011 (amid allegations of plagiarism), having never done a PhD [kandidat]. In May 2012, Putin named him Minister of Culture in May 2012, mere days after his (Putin’s) return to office after the Medvedev years, a signal that he was taking a sharply conservative turn in all things cultural, economic, and religious. In December 2012, Putin asked him to take charge of the newly created Russian Military Historical Society, an organization with an enormous state budget for the popularization (read: propagandization) of military history. It has galvanized thousands of volunteers and adherents, currently claiming to have over 10,000 members. Symbolically, the Society was modeled on one created by the last Tsar, Nicholas II, in 1907 – the Imperial Russian Military-Historical Society.

Structurally, the Russian Military Historical Society answers to the Minister of Defense, Sergei Shoygu (Putin’s lead co-planner of the Ukraine invasion), with Medinsky as its chair and Sergey Ivanov, former defense minister and KGB general, as chair of the Board of Trustees. Other leading members of the Society include leaders of business and top oligarchs like Vladimir Yakunin who considers himself to be an Orthodox oligarch and who headed the Russian Railways from 2005-2015. Yakunin has been an outspoken advocate of autarky for Russia on the grounds that such isolation will strengthen Russian businesses, including, of course, the railroads themselves.

The same year that Putin founded the Russian Military Historical Society (2012), he and Sergey Naryshkin, then the Speaker of the State Duma and now head of foreign intelligence, also oversaw the creation of the Russian Historical Society. In this case too, a prerevolutionary organization of the same name that functioned from 1866-1917 served as its inspiration. That older society had been headed by a Prince with members of the royal family as honorary chairs. In a classic example of what historian Michael Khodarkovsky has called “steppe diplomacy,” the Russian President created two societies to compete with each other and see who would more loyally serve the Crown.

Also serving Putin’s putative crown in imaginary history making is the Moscow Patriarchate of the Russian Orthodox Church, which has not said a single word about the suffering of the Ukrainian people in this brutal war.

Even as I am writing these words, Putin himself has continued to threaten Ukrainian statehood, ostensibly on the (completely fictional) grounds that the West is threatening to put nuclear weapons there. He has chosen Medinsky as chief negotiator for the Russian side, a man on record as saying “The current government, which we have been accustomed to calling Ukraine, is a historical phantom. […] And the so-called history of Ukraine is not only integrally tied to the 1000-year history of Rus/Russia/USSR – it is the same Russian history.” In this context of historical nihilism toward Ukraine, it is hard to imagine that the Russian government actually intends the negotiations to accomplish anything.