Paulina Villegas and Gabriela Sá Pessoa report on an unusually deadly election campaign in Brazil. Read the article here in The Washington Post.

RIO DE JANEIRO — Marcelo Arruda was wearing a black T-shirt bearing the face of his hero, presidential election front-runner Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, the day he was killed.

On July 9, prosecutors say, Jorge José da Rocha Guaranho drove to Arruda’s Lula-themed birthday party, blasting the song lauding President Jair Bolsonaro so loud that the guests could hear the chorus: “The myth has come and Brazil has woken up.”

Guaranho, a prison guard, and Arruda, a police officer, exchanged insults in what prosecutors called a political quarrel. Guaranho left, returned and shot Arruda to death, prosecutors say.

Guaranho was charged with qualified homicide and is expected to testify this week. His lawyer, Luciano Santoro, told The Washington Post he suffered severe beatings to the head and doesn’t remember the incident.

Analysts now see the killing of Arruda in the southern city of Foz do Iguaçu as the first in a spate of incidents in an unusually deadly election campaign.

From revolutions and revolts in the first half of the 20th century to the brutal military dictatorship in the second, Brazil has suffered a long history of political violence. But since throwing off the dictatorship in 1985, Latin America’s largest country has enjoyed relative calm at election time. Attacks have been largely limited to municipal candidates and politicians, often involving political rivals or criminal gangs.

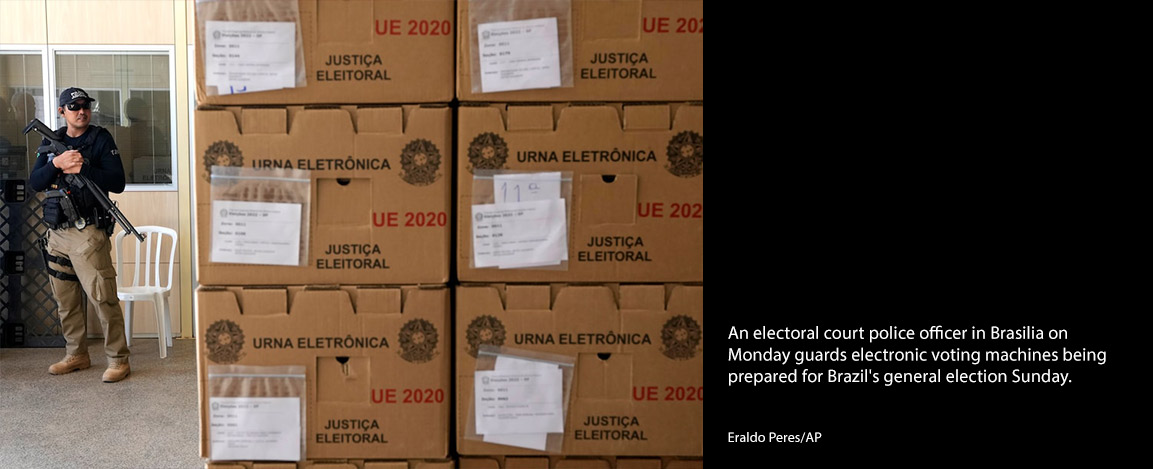

This campaign has been different. The front-runners in Sunday’s first round — Bolsonaro, the right-wing incumbent, and Lula, the left-wing former president — are the most polarizing figures in Brazilian politics. The vote has been cast as an existential contest between authoritarianism vs. democracy. Now it’s supporters of the candidates who are attacking each other, creating a new atmosphere of fear.

A man was shot inside an evangelical church in Goiânia last month after he expressed disagreement over the distribution of pamphlets urging churchgoers not to vote for leftist parties. Weeks later, police said, a Bolsonaro supporter near Confresa stabbed a co-worker to death after the man defended Lula in an argument.

On Saturday, witnesses told police, a man walked into a bar in Cascavel, 85 miles from Foz do Iguaçu, and asked who planned to vote for Lula, the newspaper O Povo reported. When a 39-year-old man said that he did, he, too, was stabbed to death. Police said Monday they had arrested a 59-year-old man in what appeared to be a politically motivated attack.

There have been several reports of Lula supporters beating “bolsonaristas” during public rallies.

In Brazil, 1 in 5 voters consider the use of violence when an opponent wins justified to at least some extent, according to a recent survey by Quaest for the University of São Paulo. About half of those believe violence is “very justified.” There’s little variation between Lula and Bolsonaro supporters.

Voters say they’re afraid to voice their opinions ahead of the election Sunday.

“I have never felt this kind of fear,” said Sheila Campello, a 68-year-old retired teacher in Brasilia, the capital.

Campello remembers the days when she, her mother and sisters wore red scarfs around their necks on election days as a show of support for the leftist Workers’ Party.

“Since the last election the joy of the election period was replaced by fear,” she said. She still wears T-shirts with portraits of her candidates, she said, but avoids going to places where she thinks she might be harassed or attacked by Bolsonaro supporters.

Lula has condemned the violence and decried a “climate of hatred in the electoral process which is completely abnormal.”

Bolsonaro initially refused to condemn Arruda’s killing, saying he would wait for the investigation to establish a motive. But after the second killing by a self-proclaimed bolsonarista, he told Noticias R7 that he “regrets any death that is politically motivated.”

“There is no point in blaming me for the actions,” he said during a presidential debate Saturday.

But analysts say Bolsonaro’s belligerent rhetoric has fueled the rancor. Four years ago, he urged his followers to “shoot the ‘petralhada,’ ” a slur for Workers’ Party supporters. As a congressman, he suggested the military should have killed more people during the dictatorship, and said only a “civil war” would bring true change to Brazil.

Bolsonaro was himself stabbed on the campaign trail in 2018. Authorities identified the assailant as Adélio Bispo de Oliveira, a former member of the Socialism and Liberty Party who claimed he was on “a mission from God.” A court ruled that he was mentally ill and couldn’t be held responsible for his actions.

Marcos Nobre, president of the Brazilian Center of Analysis and Planning, a think tank, said Brazilians at both ends of the political spectrum have grown less tolerant. But he argued that the violence from the right-wing bolsonaristas and Lula’s petistas are different.

“They are not two polar sides,” he said. “They are playing two different games. One is playing by democratic rules. The other one isn’t.”

Regardless of ideology, the common ground many Brazilians now seem to share is fear — 2 out of 3 Brazilians worry that they themselves will be victims of political violence, according to a recent poll by the Brazilian Forum on Public Safety.

Fabiano dos Santos, 42, a convenience store worker in São Paulo, said he will vote for Lula as he has always done. But this year, he said, he will not wear a red T-shirt.

“Am I afraid of suffering reprisal? Of course I am,” he said. “You can’t even put a sticker on your car anymore — you’d have your car scratched.”

Dos Santos said a friend was harassed at a train station while wearing a Brazilian flag T-shirt, often worn by Bolsonaro loyalists.

“They thought he was a bolsonarista,” he said. “The whole thing has no logic, and there was no such thing before. Now it’s like Corinthians and Palmeiras,” rival soccer teams in São Paulo.

For leaders, too, the race has turned deadlier.

The Observatory of Political and Electoral Violence in Brazil has tracked at last 214 cases of politically motivated violence this year, including 45 alleged homicides, targeting elected officials, candidates and public employees, up 23 percent from 2020.

Political scientist Felipe Borba, who coordinated the observatory’s report, tied the increase to Bolsonaro’s use of threats as an electoral tactic.

“Brazilian elections have always been polarized, but there has always been mutual respect that no candidate has ever dared to cross,” he said. “Bolsonaro is the first one to openly use the discourse of violence against his opponent.”

But historian Lilia Schwarcz, senior lecturer of anthropology at the University of São Paulo, sees historical precedent.

“Bolsonaro represents the continuation of authoritarianism and of people who think like him, that share a love of the military dictatorship and were not happy with democratization,” she said. “Now they are emboldened to express these views.”

An advertising for Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro at central bus station in Brasilia on Friday. (Adriano Machado/Reuters)

Pablo Ortellado, a professor of public policy at the University of São Paulo, sees growing intolerance on both sides.

“My concern is that it is civil society being split and increasing their intolerance against the other,” he said.

Ortellado cautioned that there is no data to prove widespread violence among citizens. But other data, he said, shows growing polarization dating back a decade, when Brazil suffered years of turmoil, corruption scandals, the arrests of dozens of government officials and the impeachment of former president Dilma Rousseff.

The environment has raised concern among military commanders, who in a meeting last month discussed plans in case of unrest on election day, according to the newspaper Folha de S. Paulo.

The Defense Ministry did not respond to a request for details.

Sá Pessoa reported from São Paulo.