John Tirman is executive director and principal research scientist at the MIT Center for International Studies and author of “The Deaths of Others: The Fate of Civilians in America’s Wars.”

Read this at The Washington Post or Listen to article

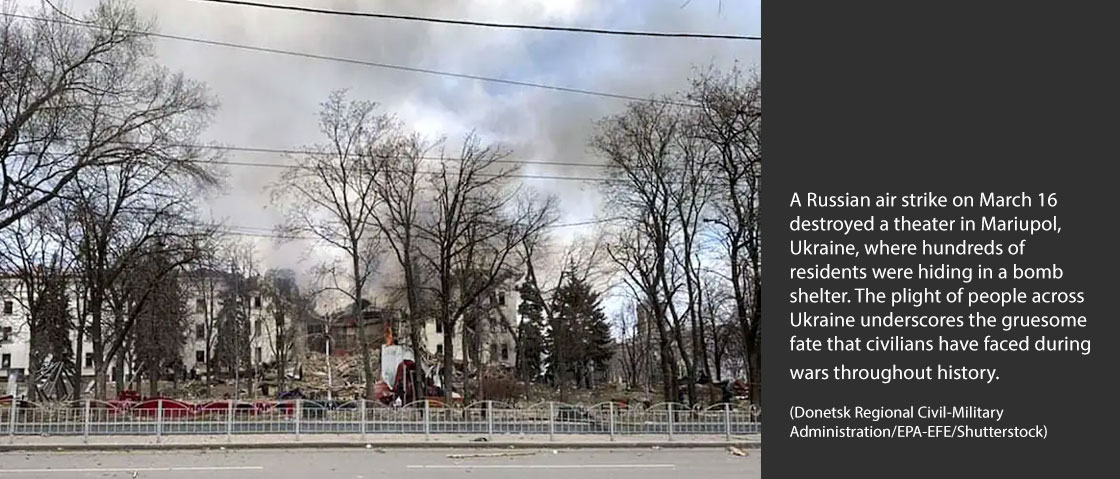

The civilian catastrophe in Ukraine is hard to witness. Every day we get new images of Russia’s bombardment of the innocent: homes blasted apart, hospitals leveled, cars and buses shredded, mothers and children dead in the streets, and in one heartbreaking photo, a bloodied pregnant woman ferried away on a stretcher only to lose her baby and her own life later.

The horror inflicted on civilians in war is nothing new. Each time a new round of barbarity strikes, we’re reminded of the suffering of civilians in past conflicts. People of all races, ethnicities, religions and nationalities from Ukraine to Iraq to Laos to Somalia have endured devastating consequences: lost families, lost homes, lost livelihoods, demolished cities and disruptions that can never be put right. Those lucky enough to survive often become part of a flood of refugees. As Russia’s attacks on Ukrainian cities intensify, it’s all but certain that civilians asleep in their homes will die in their beds.

War literature is vast, but few books zero in on the trauma of civilians. Their plight unfolds in contemporary news reporting but often is quickly forgotten. Some intrepid writers, however, have captured the struggles of ordinary folks when their homes and churches and playgrounds become targets on the battlefield. These authors reveal the anger and sadness of victims whose lives are forever changed by national leaders and political forces beyond their control. In searing detail, the books noted here show the scope of the suffering. The past experiences of an Iraqi man in Baghdad, a woman in Laos, a Bosnian Muslim — along with the ongoing bloodshed in Ukraine — illuminate the endless cycle of civilian carnage in war.

In “Night Draws Near: Iraq’s People in the Shadow of America’s War,” the renowned war correspondent Anthony Shadid drew on his knowledge of Iraq and the region to probe the human cost that began with the US invasion in 2003, which he covered for The Washington Post. Shadid, who died reporting on conflict in Syria in 2012, learned from an Iraqi artist how war had altered Baghdad. “Its morals had changed, as had its etiquette. Overrun and disfigured, it was no longer the city he had known,” Shadid wrote. “Fighting had brutalized it. . . . The culture of the gun and its unsubtle logic had come to dominate.” When U.S. troops seized Baghdad, another Iraqi man described the impact on him: “We’re against the occupation, we refuse the occupation — not one hundred percent, but one thousand percent,” he told Shadid. “They’re walking over my heart. I feel like they’re crushing my heart.”

Some Iraqis wrote their own stories, apart from the work of war correspondents, using blogs to tell the world their experiences. In one disquieting post, a father described the intense anxiety he felt when his children went off on their own to school. “The knowledge that they are in constant danger consumes you,” he wrote. “It eats you alive. You then realize that it is your love for them that is killing you. You begin to hate that love.”

Civilians trapped in the war zones of Southeast Asia in the 1960s and 1970s lived in constant danger. Between 1964 and 1975, 3 to 4 million people died in Vietnam, nearly 1 million in the “killing fields” of Cambodia and 1 million in Laos. Many books have been written about Vietnam, but it’s the rare one that shines a light on Laos. Fred Branfman recorded the stories of survivors of massive US bombing and complied them into “Voices From the Plain of Jars: Life Under an Air War.” His book helped expose the secret US campaign in which 2 million tons of bombs were dropped on the Laotian people. The survivors describe the destruction of their idyllic rural life, the napalming of their villages and the slaughter of workers in the fields. “Our lives became like those of animals desperately trying to escape their hunters,” recounted a 30-year-old woman. Sons and daughters, mothers and fathers “would die from a single blast.” She told Branfman, “It is only the innocent who suffer.”

Ben Rawlence conveys a similar harsh message in “City of Thorns: Nine Lives in the World’s Largest Refugee Camp.” Worldwide, according to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, some 82 million people had been forcibly displaced from their homes by the end of 2020, most often by war. Yet the literature that reveals their day-to-day scramble for survival is quite slim. Rawlence, then a human rights worker in East Africa, spent years chronicling the daily lives of refugees in the Dadaab camp in Kenya. This site, once the largest refugee camp in the world, has accommodated people fleeing the civil war in Somalia for 30 years.

Rawlence traced the stories of nine individuals in the Dadaab camp to illuminate their unforgiving struggles but also their resilience and hopefulness. The inhabitants grappled with overcrowding and disease; sometimes food and water were in short supply. Some residents sneaked out of the camp to take jobs in Kenya as undocumented workers. The slivers of hope were fragile. Yet refugees still came. “To flee [Somalia for Dadaab] one needed three things: money, courage, and imagination,” Rawlence observed. “Money, because nothing in Somalia was free. . . . Courage, because the route south was booby-trapped with checkpoints, lawless militias and bandits. . . . And imagination because, for a mind shaped by the confusion of war, the ability to imagine that life might be different or better elsewhere is an uncommon leap.”

In “The Key to My Neighbor’s House: Seeking Justice in Bosnia and Rwanda,” Elizabeth Neuffer explored the complex road to justice for victims of genocide in Bosnia and Rwanda in the 1990s. Neuffer, a war correspondent who was killed in Iraq in 2003, brought the horror of ethnic cleansing into sharp relief in her description of a Serbian-run prison that operated as a concentration camp. She recounts the experience of a Bosnian Muslim named Hamdo who experienced this “sadistic underworld . . . where days and nights were measured by a prisoner’s ability to avoid starvation, torture, rape, or death.” For women, there was constant sexual assault. “After forcing the women to clean the blood from the walls,” Neuffer wrote, “the guards assaulted them. If they didn’t cooperate, they’d join the corpses they saw on a daily basis being thrown over the hedges or stacked like cordwood on the grass.”

Sometimes trauma in a war zone comes not in a constant barrage but in a drip drip drip of lurking menace, punctuated by sudden outbursts of violence. Anna Badkhen captured this type of everyday life, where beauty and bloodshed mingle, in “The World Is a Carpet: Four Seasons in an Afghan Village,” her portrait of a tiny village in northern Afghanistan. The village of Oqa survives on carpet weaving but can’t escape the threats of the US war, heroin addiction, local violence and the presence of the Taliban. But life goes on with the steadiness and determination of carpet weaving.

After a summer of violence, Badkhen wrote, “somehow the bloodshed and fear . . . seemed only lightly traced upon the fixed topography of the land, the scarring of these latest war crimes and threats impermanent like drifting sand upon the immutable canvas of the plains and mountains, ready to be erased and rewritten anew the next summer, and the next and the next. For the most part, life went on as it had forever.”

War brutalizes ordinary people, and our instinct may be to turn our heads, if only for self-preservation. At great risk, these authors have taken it upon themselves to immortalize this grim reality, so the world will not look away.

John Tirman is the executive director and principal research scientist at the MIT Center for International Studies and the author of “The Deaths of Others: The Fate of Civilians in America’s Wars.”