It is difficult to know if Americans would care more if they knew more. But one modest remedy is for Congress to empower an agency to calculate the human costs of war in real time and hold regular hearings that demand accountability from the president for the consequences of US war making, writes John Tirman in a recent opinion piece first published here. Tirman is executive director and principal research scientist at CIS. He is author of The Deaths of Others: The Fate of Civilians in America's Wars. He is a DAWN fellow.

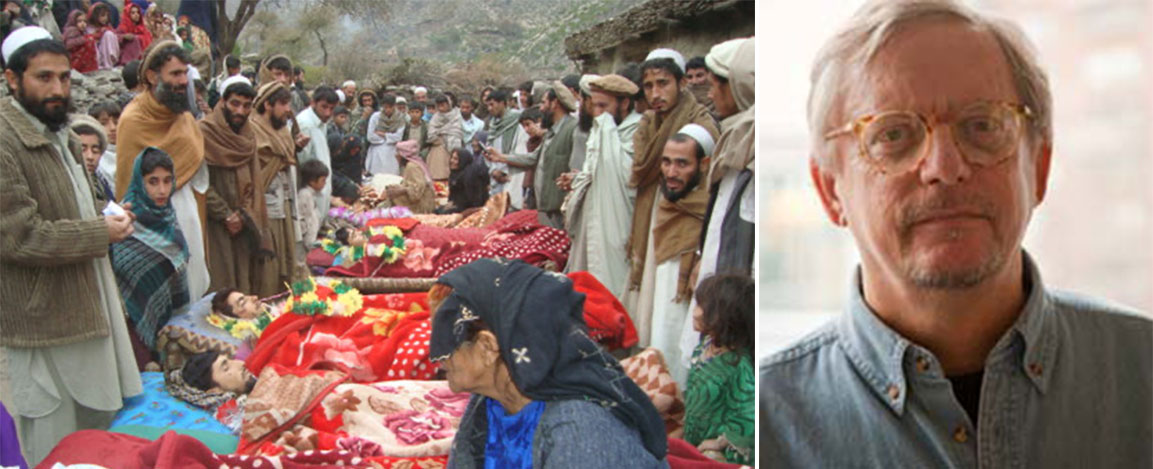

Image far left is people of Narang district mourning for the students killed in a night raid on December 27, 2009. Courtesy Wikipedia Commons.

The US evacuation from Kabul in August accidentally highlighted how little Americans pay attention to civilians in war zones. Suddenly, the American news media discovered dozens if not hundreds of stories about Afghans in distress, women facing suppression of their rights and girls again denied an education, or worse.

Top American journalists like Richard Engel of NBC News expressed sorrow at the abrupt retreat. "It is deeply depressing to watch what could be among the final Afghans loaded up and flying out of their country," he tweeted on Aug. 25. "Afghans had hope. Now millions live in fear. A humiliating end for the US in Afghanistan."

There was little of this focus on human security and the actual costs of war over America's two decades in Afghanistan. The major US news networks, including Engel's, dedicated a total of five minutes of coverage to Afghanistan in 2020. This is an old pattern in American wars, where public interest is high and supportive when wars are started, but those sentiments are overtaken by indifference when things go awry and the US interests at stake begin to look doubtful. It happened in Korea, Vietnam, Iraq and—many years ago—in Afghanistan, well before it became America's longest war.

It is difficult to know if Americans would care more if they knew more. But one modest remedy is for Congress to empower an agency to calculate the human costs of war in real time and hold regular hearings that demand accountability from the president for the consequences of US war making.

Close to a million Iraqis have died in the two wars and more than decade of sanctions that have ravaged the country for 30 years, starting with Operation Desert Storm. Such an estimate is based on household surveys that provide a fairly accurate picture of war's devastation. In Afghanistan, we don't know the toll—in mortality, displacement, immiseration, social dissolution—because no one has done the work to find out. That, in itself, is a symptom of indifference. Estimates using morgue numbers or border crossings are almost always too low. Less quantifiable impacts of destroyed markets or unusable roads or stolen futures of the young go wanting for attention, even as they are the daily reality for most Afghans.

Journalist Anand Gopal made this point in his recent report from the Afghan countryside in The New Yorker. The American presence in the country's rural areas, where more than 70 percent of Afghans live, was brutally violent. When US artillery or air strikes would kill innocent civilians in isolated villages—which was frequent—it was a bonanza for Taliban recruitment. The endless cycles of violence meant that the Taliban was flush with young men ready to fight the occupiers and the corrupt central government in Kabul. "This is not 'women's rights' when you are killing us, killing our brothers, killing our fathers," a woman in one rural village told Gopal. "The Americans did not bring us any rights," said another. "They just came, fought, killed, and left."

So much of US foreign policy is dismissive of this indelible scar of human costs from America's wars. Military and political leaders should want to know what is occurring on the ground of these distant battlefields.

The rapid collapse of the Afghan army and the US-backed government was a "surprise" only because so little was known about what was besetting most Afghan civilians outside the confines of Kabul and other cities. What was known was brushed aside by US officials keen to make the mission appear far more successful than it was.

And this is not something that only just happened, which is another peculiarity of the shortsighted US media coverage of Afghanistan. The writer Anna Badken chronicled the despair gripping the Afghan countryside a decade or more ago. "The road to women's wellbeing begins with food security, infrastructure that works and a government that protects them against sectarian violence," she wrote in 2014, in one of her many dispatches from the country, this one from the village of Kampirak. "But none of this is in sight. The country is spinning toward more bloodshed; food remains scarce, infrastructure abysmal; the Afghan society, by and large, does not welcome education for women," she added. "The way the women of Kampirak see it, no matter which band of armed men patrol their deeply fissured land, they will go on surviving the way they have for centuries, abused and abandoned by a succession of indifferent governments."

She told me years ago that once the Americans left, the Taliban would take over quickly.

So much of US foreign policy is dismissive of this indelible scar of human costs from America's wars. Military and political leaders should want to know what is occurring on the ground of these distant battlefields. Instead, they and other observers tend to view these wars as another episode of gamesmanship, both internationally and domestically. The obsessive chattering about "US credibility" after last month's evacuation from Kabul is a vivid example of the magical thinking that dominates public discourse.

The years-long destruction of these societies and people by American forces—or indirectly through military assistance, as with the more recent Saudi-led war in Yemen—are the most damning criticism of these interventions, and so they must be shunted aside as "collateral damage" in the schemes of US grand strategy. Public indifference braces Washington's delusions of social progress and winnable wars.

It is difficult to know if Americans would care more if they knew more. But one modest remedy is for Congress to empower an agency to calculate the human costs of war in real time and hold regular hearings that demand accountability from the president for the consequences of US war making.

Dwight Eisenhower once said, "I hate war as only a soldier who has lived it can, only as one who has seen its brutality, its futility, its stupidity." If we don't question war's brutality, futility and stupidity before the last soldier boards the last plane, we will have learned nothing while condemning millions more to a wretched life