This appeared orginially here.

The US defense effort consumes roughly three-quarters of a trillion dollars per year and makes up a quarter of all Federal spending and half of all federal discretionary spending. Because resources are scarce relative to plausible projects and money is fungible, the defense effort should, like other federal spending, be subjected to close scrutiny. This is especially true today, given the extraordinary federal expenditures incurred to address the COVID-19 pandemic and the federal debt that funded them.

It is tempting to cut acquisition programs that have unusually high price tags, checkered development histories, or esoteric rationales, whenever one reviews the defense budget with an eye toward efficiency. One thinks currently of the F-35 tactical combat aircraft or the land-based ICBM modernization program dubbed the Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent. It is more difficult than one might think, however, to find enough such programs that are politically vulnerable to elimination to save a lot of money over a sustained period. At bottom, significant and sustained cuts, reallocation, or additions to US defense spending should be considered in light of US grand strategy—the political-military theory that we have of how to produce security for the country.[1] Here, I will argue for a strategic reconsideration of one major element of the US defense effort—the commitment to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. I will show that major reforms in how the US fulfills its alliance commitment can save as much as $70 billion to $80 billion per year.

It is time for a true division of labor within the Atlantic alliance. A suggestive passage from the Biden administration’s new strategic concept points the way: “We will work with allies to share responsibilities equitably, while encouraging them to invest in their own comparative advantages against shared current and future threats.”[2] The comparative advantages that the United States brings to the alliance involve intelligence (on which it spends $80 billion a year), offensive nuclear forces (the tools of the much vaunted nuclear umbrella), and naval power (especially the most costly and complicated assets—nuclear attack submarines and nuclear-powered aircraft carriers). Europeans should specialize in missions in which they are inherently more efficient by reason of proximity to plausible military challenges—direct defense of European territory with ground and supporting tactical air forces. I have demonstrated elsewhere that they have adequate military personnel and ground and air combat units to fulfill this mission.[3]

A grand strategy is a political-military means-ends chain. It is a foreign policy establishment’s theory of how to create security for the country it leads and serves. Grand strategy assesses and prioritizes threats and opportunities. Priority is a particularly important concept. It is best to be very strong in those areas where analysis determines the threats to US strategic interests are greatest. Broadly speaking, the United States has since the start of World War II tried to ensure that there is no hegemonic power in control of all the resources of Europe, on the theory that such an agglomeration of resources could threaten the United States directly. First Nazi Germany and then the Soviet Union were sufficiently powerful to threaten the conquest of Europe. The United States applied the same logic in Asia, though the risk there of a successful hegemon waned with the defeat of imperial Japan and has only returned with the rise of China.

The threat of a hostile power controlling Europe is now very low, whether or not the United States remains committed to Europe’s defense. Cold War containment succeeded beyond the US foreign policy establishment’s wildest dreams. The Soviet Union was not only prevented from achieving hegemony in Europe; it collapsed. Russian power is considerably less than half of what the Soviet Union could muster. Meanwhile, the European powers shattered by World War II have recovered their economic vitality. The European Union—an admittedly unusual assembly of nation states—musters five to 10 times the economic power of Russia (depending on whether gross domestic product at purchasing power parity or at market exchange rates is the relevant comparison). The EU has three times Russia’s population. Indeed, the members of the European Union collectively outspend Russia on defense by a factor of three at market exchange rates.

If non-US NATO is the relative standard, Canada, Turkey, Norway, and the UK bring total non-US alliance military spending to $300 billion, nearly five times that of Russia. Even a purchasing power parity comparison, which would give Russia credit for the possibility that it may be buying its weapons and personnel at bargain prices, yields a two-to-one spending superiority in non-US NATO’s favor. One could argue on the basis of these figures, as I have done elsewhere, that Europeans should be left entirely to defend themselves.[4] Here I assert a less revolutionary but still strongly reformist position: Europeans can and must carry a much bigger share of the responsibility for their own defense.

The principal threat facing NATO Europe today is Russia. When the Soviet Union collapsed, Russia inherited much of its military capability, which promptly atrophied due to the concomitant economic collapse. Under Vladimir Putin, Russia has invested steadily in rebuilding its military capability, and today Russia is an imposing military power. Though much less capable than the preceding Soviet Union, Russia’s current nuclear and conventional forces are real. NATO thus faces the task of deterring both nuclear and non-nuclear threats. Though France and Britain both possess national nuclear capabilities, the alliance as a whole leans heavily on the United States for “extended nuclear deterrence.” The alliance also faces non-nuclear naval threats in the Black and Baltic Seas, and in the North Atlantic. Russian ground forces in Russia border NATO member states Estonia and Latvia, and—via the enclave of Kaliningrad—Lithuania and Poland. From a military point of view, NATO planners almost surely expect Russian ground forces would have easy access to Belarus during any conflict, which would further affect these NATO member states.

Though NATO’s plans for defense against a range of possible Russian threats are secret, it is clear from the present pattern of NATO exercises, from US military preparations, and from public information that the US military is expected to play a huge role in the direct defense of NATO European nations. In the event of a major Russian military mobilization along the borders of NATO nations, or in the event of an actual attack, large numbers of US naval, air, and ground forces would flow to Europe. US strategic nuclear forces would go on high alert. US nuclear attack submarines would surge into the Barents Sea to hunt, and if they find them, destroy Russian nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines. Though the United States enjoys a comparative advantage in some of these missions, the Europeans could easily take up others. Given scarcity of resources, the US should insist they do so.

As noted above, the European members of NATO have the financial and demographic resources to defend themselves from Russia. Skeptics worry that without US leadership they won’t, or that the United States has certain key capabilities that cannot be replaced in the medium term.[5] Though I believe otherwise, I take these critiques at face value for this analysis. In this proposal, the United States would remain in the alliance and continue to provide “extended nuclear deterrence.” Nobody really knows how this works, but the main way to accomplish this is to ensure that some US forces would inevitably be in the war from the outset of a Russian challenge.[6] To reinforce this message, small US contingents of special operations forces can exercise more or less regularly with European military forces, especially those most proximate to Russia. The United States would also commit its naval and amphibious power to the defense of the North Atlantic sea lanes and assist Norway directly, because its coastline, bases, and intelligence gathering installations are important to the defense of the Atlantic. Finally, the United States would contribute “intelligence” to the NATO command structure: Small staffs and dedicated communications links would remain attached to key NATO headquarters for this purpose.[7]

The United States would, however, divest itself of its current capabilities to defend European land and airspace directly. No major US ground or tactical air units would be retained for the purpose of European defense. Direct military defense of Europe’s borders and most of its airspace would become a European mission. To ensure that Europeans feel this responsibility, the United States should insist on a major change in NATO’s command structure. During the Cold War, the United States held NATO’s two major commands—the Supreme Allied Commander Europe (SACEUR) and the Supreme Allied Commander Atlantic (SACLANT). The Alliance should return to this structure, but a European should be SACEUR and a US admiral SACLANT.[8]

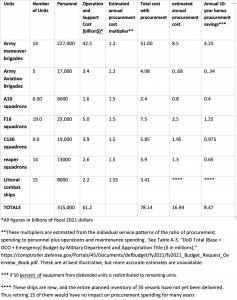

The “division of labor” force structure reductions would remove the following units:

Army

- Fourteen mechanized, light mechanized, and infantry brigades of the active US Army and their combat support and combat service support.

- Five Army aviation brigades.

Air Force

- Seven A10 close air support squadrons.

- Fourteen Reaper, remote piloted aircraft reconnaissance/attack squadrons.

- Twenty F16 multipurpose fighter/ground attack squadrons.

- Eight C130 tactical airlift Squadrons

Navy

- Fifteen “littoral combat ships,” which I hypothesize would be allocated to escort ships laden with army equipment across the Atlantic, though in all likelihood much more capable and expensive ships would likely be allocated to this mission.

The US Defense Department does not offer much detail on how it plans to allocate forces. So I needed to estimate which forces can be cut in line with the division-of-labor concept. One way to think about this is simply by large theaters of operations. The Defense Department now speaks in terms of competition with two great powers, Russia and China. On these grounds, it is reasonable simply to divide US ground forces in half, estimate the tactical combat and airlift aircraft the US Air Force would normally commit to their support, and add a few other forces necessary for inter-theater movement. Because it is hard to imagine that the US Army has much of a role in Pacific conflict with China, this heuristic is conservative. That said, the Defense Department might argue that US ground forces and associated tactical air forces actually have four possible missions: Europe, the Persian Gulf, the Korean Peninsula, and somewhere else in Asia. Even if this argument were accepted, there remains the question of how much and what kinds of risk the United States needs to spend defense dollars to limit. How many simultaneous wars does the United States need to be able to fight? Are these regions equally important and equally demanding on ground forces? These are questions of judgment.

Given the significant capabilities of the NATO allies, I judge the risk of cutting these forces to be low. Given the fading importance of Persian Gulf energy supplies, any plans to refight a major war there are mistaken. And given the relatively limited utility of ground forces in a conflict with China, it is difficult to see the point of retaining large ground forces for that purpose. Finally, though citizens of the Republic of Korea might not like to hear it, they have funded a large and capable conscript army that ought to be able to defend the narrow front of the Peninsula against aggression by North Korea, a poor country with half the population of the south. The risk to US interests of the force structure reductions suggested below is modest.

In the table below I detail the US military units that could be disbanded, and the amount of money that could be saved, by this new division of labor.

The US Congressional Budget Office has developed the “Interactive Force Structure Tool” to facilitate independent analysis of the budgetary implications of major force structure changes.[9] Unfortunately, the tool assesses only the operations and support costs of various units; it does not assess capital costs. To assess capital costs, I have relied on average ratios of procurement spending to operations and support spending by service as I have calculated from the Defense Department comptroller’s annual budget reports.[10] The tool also does not address infrastructure costs. This proposal would significantly reduce the size of the US military—by 315,000 uniformed personnel, or 23 percent of the active force—so the US base structure could also contract, with some savings. Reductions of this magnitude could not take place overnight but could be done over a single presidential term. A similar reduction was achieved at the end of the Cold War in roughly four years, between 1989 and 1993.[11] A four-year interval would also provide the European members of NATO plenty of time to “tune up” their forces to match their increased responsibilities—mainly to increase combat readiness and reserves of spare parts and munitions needed to sustain intense conventional conflict for at least 30 days.

US allies must begin to take more responsibility for their own defense, because the United States faces many demands on its resources. Direct defense of Europe’s land borders is well within the capabilities of existing European force structures. Europeans may prefer that the United States carry the responsibility for this mission, but that is different from inevitable dependence on the entire panoply of forces that the United States now has dedicated to Europe. NATO is a venerated alliance in the US national security establishment, and supporters of the alliance will oppose this change, even though it leaves the alliance intact and the United States deeply engaged. Innovation is always difficult, but it is easier when resources grow scarce, and they are growing scarce for the Defense Department. Such a transformation would yield major financial dividends for the United States at little additional risk. The European allies will not address these shortfalls unless the United States makes alliance transformation a priority. The Biden Administration should lead this effort.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

Meijer H and Brooks SG (2021) “Illusions of Autonomy: Why Europe Cannot Provide for Its Security If the United States Pulls Back,” International Security 2021. doi: https://doi.org/10.1162/isec_a_00405,

Posen BR (2020) “Europe Can Defend Itself,” Survival, International Institute for Strategic Studies, London, December/January

Posen BR (2021) “In Reply: To Repeat, Europe Can Defend Itself,” Survival, IISS, London, February/March, 2021.

Endnotes

[1] Even the F-35 and ICBM programs depend on strategic rationales. The former serves the rationale that clear and vast military technological superiority contributes greatly to deterrence. The latter serves the deterrence rationale that no great power can think about a nuclear first strike against the United States, if that strike would leave hundreds of hard-target-killing missiles intact, but to attack those missiles in the hope of eliminating them would mean hundreds of nuclear explosions over the United States, which would surely make US decision makers sufficiently angry to retaliate massively with surviving bomber or submarine based nuclear weapons. The theory is that the ICBM in particular contributes importantly to deterrence by forcing an adversary to start a nuclear war with a large strike rather than a small one. The bet is that the heightened prospect of large-scale retaliation would discourage any strike at all, large or small.

[2] See “Interim National Security Strategic Guidance,” March 03, 2021, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/03/03/interim-national-security-strategic-guidance/.

[3] See Posen 2020 and Posen 2021.

[4] See Posen 2020.

[5] In “Illusions of Autonomy: Why Europe Cannot Provide for Its Security If the United States Pulls Back” Meijer and Brooks (2021) argue that the Europeans, if forced to organize their own defense under the auspices of the European Union, lack among other things, the command, control, and intelligence assets to organize a defense against a Russian attack and could not develop these organizational and material capabilities in short order. I agree that the EU as an institution is still unready to assume these responsibilities, but have argued that the material wherewithal exists in Europe for it to do so. But this particular proposal is responsive to their concern. NATO’s command structure would remain intact, and the United States would retain dedicated units to connect European militaries to the massive US intelligence effort.

[6] The United States also maintains as many as 200 nuclear bombs forward deployed in Europe for use by its own tactical aircraft and those of Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany, Italy and Turkey. Whether this deployment is a net security positive for the Alliance is an open question. Aside from what the United States will spend to modernize these munitions, the actual cost to European militaries for the aircraft needed to deliver them, to store and protect these munitions, to maintain command and control in peace and war, to have in place dispersal plans for these forces to improve their survivability in any crisis, and the dedicated aerial tankers and other combat aircraft dedicated to support tactical nuclear missions, are unknown, but probably substantial. Given scarce resources, the tactical nuclear mission detracts from NATO’s conventional capability. These nuclear bombs do remind the Russian decision makers that conventional war in Europe involves nuclear risks, but there are probably more cost-effective ways to remind them of this fact. See “A Conversation with Rose E Gottemoeller,” Council on Foreign Relations, May 3, 2019 https://www.cfr.org/event/conversation-rose-e-gottemoeller for an unusually candid discussion of the role of these nuclear weapons in Europe and also the way they draw on the resources of countries whose aircraft are not formally committed to the nuclear delivery mission.

[7] I have not tried to assess the costs of these remaining forces, but this should not amount to more than a few thousand military personnel, and thus they should be low.

[8] Barry R. Posen, “Towards a More Responsible Europe: Radical Reform of the Transatlantic Relationship is in the US National Interest,” in Michiel Foulon and Jack Thompson, eds., “European Strategy in an Era of Increasing Geopolitical Competition: Challenges and Prospects,” The Hague Centre for Strategic Studies, forthcoming, August 2021.

[9]See: https://www.cbo.gov/publication/54351#info as accessed 7/9/21

[10]See Defense Budget Overview: “Irreversible Implementation of the National Defense Strategy,” REVISED MAY 13, 2020: A6-7, https://comptroller.defense.gov/Budget-Materials/Budget2021/

[11]See the collection of annual DOD personnel reports at https://dwp.dmdc.osd.mil/dwp/app/dod-data-reports/workforce-reports .