In August, International Affairs has teamed up with the Future Strategy Forum for the ‘Pandemic Politics’ series on US politics and the COVID-19 pandemic. This week in Pandemic Politics, Eleanor Freund and Leah Matchett’s introduction, as well as Bob Qu’s, Autumn Perkey’s, and Lauren Sukin and Kaitlyn Robinson’s blogposts discuss COVID-19 and the US military. The original post is here.

During the coronavirus pandemic, the military has stepped up to help in a surprising way: with bodybags. The Pentagon has confirmed that it will be providing as many as 100,000 body bags to the US Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to assist in managing the death toll from the pandemic. The threat posed by the pandemic is not one that is suited to traditional military solutions, begging the question: what is the role of the military in responding to a national crisis that has killed more Americansthan every war from the Korean War onwards…combined?

In this section of the Pandemic Politics series, three members of the Future Strategy Forum cohort grapple with the role of the military in the COVID-19 crisis. Bob Qu argues that the US Marine Corps’ recent restructuring plan takes innovative and bold steps that other services must copy to meet the economic challenge of COVID-19. The other two pieces focus on the question of when the military should get involved, and the importance of standards of behaviour. Autumn Perkey argues that the military should not be at the forefront of the COVID-19 response, suggesting that importing a sense of the nation as a ‘battlespace’ is harmful both to the US and the armed forces. In a counterpoint to this piece, Lauren Sukin and Kaitlyn Robinson suggest one area where importing military norms that hold sway in overseas deployments back to the United States would be beneficial: rules of engagement. They focus on recent protests in the United States and the similarities between the police and the armed forces.

In addressing relationship between the US military and the COVID-19 crisis, it is important to note that there are two key questions: how can the US military affect the current national crisis and how is the crisis affecting the military? The military has been involved in messaging, logistics and direct support of communities affected by the pandemic. At the same time, the realities of living with an infectious disease are challenging basic assumptions about military budgets, force readiness and training.

How is the military being impact by the COVID-19 pandemic?

The most immediate concern COVID-19 raises for the military is the astronomical hole it has created in the federal budget. Since the beginning of the pandemic, many analysts have suggested that COVID-19 and its attendant economic impacts could generate significant pressure to reduce military spending (and indeed it already has). The US has spent two trillion US dollars to fund its pandemic emergency relief programmes and the Congressional Budget office recently reported increased outlays and decreased revenue as a result of COVID-19. In May 2020, for example, the federal budget deficit was twice the May 2019 amount. Increases in the national debt, coupled with pressure to overhaul the health system, could lead to significant pressure to reduce military spending. Indeed, Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont is spearheading an effort to cut ten per cent of annual Pentagon spending in order to increase funding for health care, housing, child care and education in places experiencing a poverty rate over 25 per cent.

Next to the budgetary concerns, there are also questions of how to maintain force readiness and military training in the face of infectious disease. The US military replaces between 15 and 20 per cent of their total personnel every year. However, boot camp does not lend itself easily to social distancing — and in April the army had a cluster of 50 cases at its Fort Jackson training facility. This is particularly noteworthy when the US military replaces between 15 and 20 per cent of their total personnel every year. In response, the army recently paused basic training for two weeks to put in place measures against coronavirus exposure and it subsequently restarted training at what officials called ‘a reduced capacity’ — though there is little idea of what this means.

Once training has been complete it is difficult to quarantine soldiers entirely, leading to new risks of infection. By April, 26 of the US’ battleships had positive cases of coronavirus. The USS Theodore Roosevelt was the most visible among these, being forced to dock in Guam in the face of a massive outbreak of COVID-19 on board that would eventually lead to 1,000 infections and one death. Similarly, France’s Charles de Gaulleaircraft carrier was recently forced back to port after roughly 40 of its crew showed signs of COVID-19.

Many of the readiness questions posed by the pandemic are solvable, particularly by an institution like the military which plans for force attrition. However, cases like the USS Theodore Roosevelt, where Captain Brett Crozier was fired for writing a letter to navy officials asking for help in dealing with the pandemic, have raised questions about how military leadership will respond to these challenges.

How can the military contribute to the response?

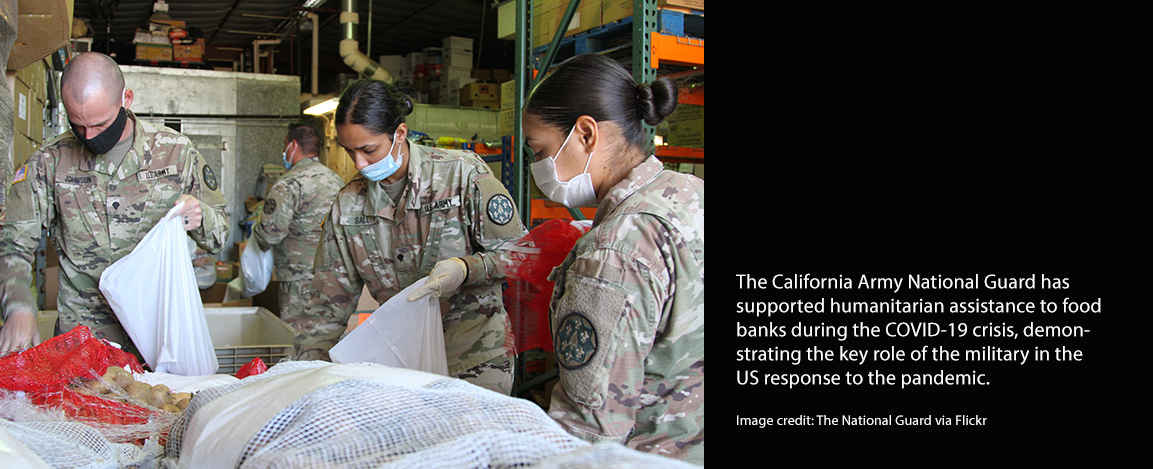

The military also stands to have a large effect on COVID-19 response efforts. In the United States, military involvement in pandemic response has included the deployment of 43,000 members of the army and Air National Guard, the assignment of 4,000 doctors and medical personnel to support hospital capacity, the US Army Corps of Engineers’ involvement in creating 15,800 additional beds, and the use of four army field hospitals. This mirrors the use of the military in coronavirus responses across the globe, including in Germany, France and China.

As an institution, militaries are generally proficient in logistics and some have benefited from experience responding to prior public health crises like Ebola and SARS. However, this begs the question about to what extent the military should be involved in pandemic response. The need to turn to the military to help respond to COVID-19 reflects comparative underinvestment in civilian institutions. The military is not a substitute for a robust public health infrastructure or for competent civilian agencies.

In the following three pieces some of these questions are interrogated, asking how COVID-19 challenges the role of the military overseas and domestically. Qu, Perkey, and Sukin and Robinson offer compelling early answers to essential questions about how this pandemic will affect the military, and ultimately, us all.

Eleanor Freund is a PhD student in security studies and international relations at MIT. She holds an MA in global affairs from Tsinghua University in Beijing, where she was a Schwarzman Scholar, and a BA in political science from the University of California, Berkeley. Her research interests include Chinese foreign and military policy, nuclear weapons, arms control and the politics of authoritarian regimes.

Leah Matchett is a PhD student in political science at Stanford University. She holds a BA in global studies and geology from the University of Illinois and an MPhil in international relations from the University of Oxford. She is a Marshall Scholar and was named the Nuclear Non-proliferation Education and Research Center’s Most Exemplary Fellow.