Going abroad in search of monsters to destroy won't save Americans from pandemics, but it does risk entangling the United States in a cold war with the world’s second largest power. We stand on the brink of an even more destructive and less justifiable mistake than the post-Sept 11 crusade, write the co-authors in this New York Times opinion piece.

Rachel Esplin Odell is a PhD candidate in political science at MIT. She currently is a research fellow at the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft and an international security fellow at the Belfer Center at the Harvard Kennedy School. Stephen Wertheim is deputy director of research and policy at Quincy and a research scholar at the Saltzman Institute of War and Peace Studies at Columbia.

Before the pandemic, before the Great Recession, before proliferating hurricanes and fires, the United States began a global war on terrorism. Its leaders fixated on a shadowy enemy abroad as life at home crumbled for millions of Americans. The war on terrorism did not end terrorism; the war itself became endless. What it did shatter was the myth that a triumphant United States could bend the world to its will.

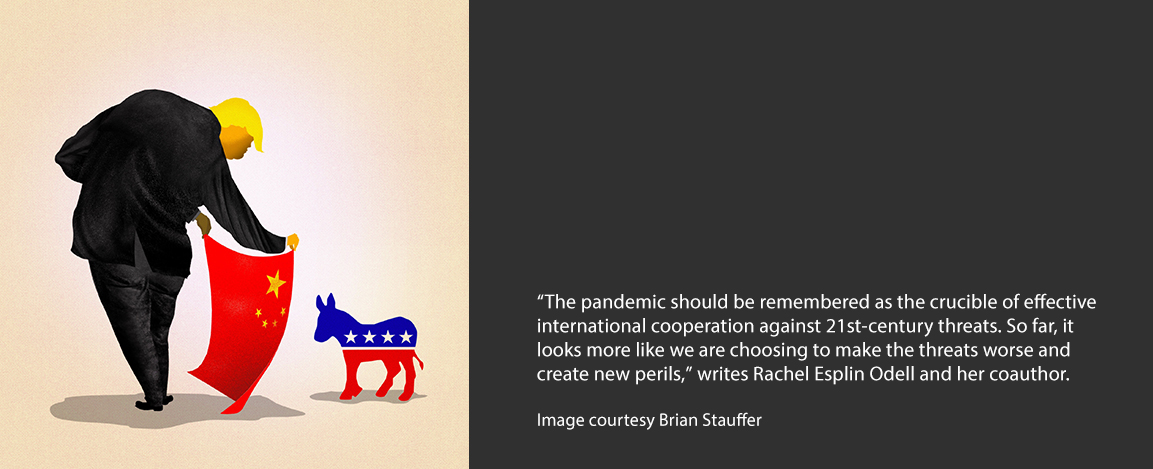

But the myth may be roaring back, albeit in a less righteous, more vicious guise. Though the new enemy is a virus, even less susceptible to verbal and physical firepower than terrorists, the Trump administration appears to be setting its target on a foreign power: China, where the outbreak appears to have started but which is hardly responsible for the United States being the most infected country in the world.

As the pandemic spread in the United States in March, President Trump began to castigate Beijing for failing to contain and report on “the Chinese virus.” Now Secretary of State Mike Pompeo is declaring that there is “a significant amount of evidence” that the virus originated in a Chinese laboratory, though he has provided no proof. The accusation, although doubted by scientists and intelligence agencies, may lead the public to blame China for the pandemic, much as the George W Bush administration, through suggestion more than outright lies, convinced seven in 10 Americans in 2003 that Saddam Hussein of Iraq was likely involved in the Sept 11 attacks.

Going abroad in search of monsters to destroy won't save Americans from pandemics, but it does risk entangling the United States in a cold war with the world’s No 2 power. We stand on the brink of an even more destructive and less justifiable mistake than the post-Sept 11 crusade.

On one level, the administration’s gambit looks like classically Trumpian bluster. Seizing on a grain of truth—China, at a minimum, covered up evidence of the outbreak and was too slow in sharing complete information with international health authorities—Mr. Trump seeks to avoid responsibility for a pandemic that the White House was slower still to take seriously. Even if it walks back its most extravagant claims, the administration could acquire a cudgel for the November election. The largest pro-Trump PAC is already calling Joe Biden “Beijing Biden,” laying a trap for him to either defend China or bash it harder than Mr. Trump. Either way suits the president.

Blaming China also emanates from Mr. Trump’s punitive vision of world affairs. Having vowed to turn the tables on an array of foreigners supposedly exploiting the United States, the Trump administration is now considering demanding reparations from China and suspending its sovereign immunity to allow it to be sued for virus-related deaths. Such measures would invite swift retaliation and untold lawsuits against the United States. They would also undermine the cooperation needed to develop and manufacture coronavirus treatments, to say nothing of worsening the economy.

The larger danger, however, goes beyond President Trump and predates the pandemic.

In recent years, China hawks have cited a cocktail of geopolitical fears, economic grievances and human rights violations as causes for alarm, leading some Obama administration veterans to arrive at the expansive conclusion that engagement with Beijing had failed. While balking at Mr Trump’s trade war, much of the bipartisan establishment embraced his administration’s notion, laid out in the 2017 National Security Strategy, that China is a threat requiring a strategy of full-spectrum competition.

Last summer, several scholars warned that a “new cold war” between the superpowers could plunge the world into an intense military rivalry and thwart necessary cooperation against planetary threats like global warming, disease and deprivation.

Then, in the autumn, the powers stepped back from the brink. Mr Trump himself seemed more interested in making a trade deal than pursuing a geopolitical struggle. The American public had bigger worries than the China peril. In the presidential primaries, Democratic candidates talked more about ending interminable conflicts and tackling climate change than confronting China. But now the pandemic may be resurrecting the Cold War.

Democrats, and Republicans who truly put American security first, face a choice. Joe Biden in particular will decide whether to lead his party into Mr Trump’s trap or play a different game. Attempting to out-hawk far-right hawks failed Democrats in the war on terrorism, leaving Mr Biden with the stain of having supported the Iraq war. More important, a bipartisan addiction to military action and fearmongering failed the country.

Mr Biden now has the opportunity to show he learned from past mistakes by speaking out against an unnecessary cold war with a power strong enough to endanger Americans’ security and well-being. Decades from today, the pandemic should be remembered as the crucible of effective international cooperation against 21st-century threats. So far, it looks more like we are choosing to make the threats worse and create new perils.

MIT PhD candidate in political science Rachel Esplin Odell (@resplinodell) is a research fellow at the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft and an international security fellow at the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs at the Harvard Kennedy School. Stephen Wertheim (@stephenwertheim) is deputy director of research and policy at Quincy and a research scholar at the Saltzman Institute of War and Peace Studies at Columbia.