Recent articles that warn of the growing risk of Chinese aggression in the Taiwan Strait have become so common that they have created something of an invasion panic in Washington—one that is damaging to both the United States’ and Taiwan’s interests according to Rachel Esplin Odell and Eric Heginbotham.

This piece was part of a larger article debating Beijing's threat to Taiwan, which appeared in the September/October 2021 issue of Foreign Affairs.

DON’T FALL FOR THE INVASION PANIC

Oriana Skylar Mastro’s article “The Taiwan Temptation” (July/August 2021) is one of many recent articles that warns of the growing risk of Chinese aggression in the Taiwan Strait. Such articles have become so common that they have created something of an invasion panic in Washington—one that is damaging to both the United States’ and Taiwan’s interests. Anxiety about impending Chinese aggression was part of what drove Washington in recent years to weaken its long-standing “one China” policy by lifting some restrictions on official interactions between it and Taiwan. It also undergirds recent calls for Washington to abandon its policy of “strategic ambiguity” about whether it would defend Taiwan against a Chinese attack.

Although Mastro does not explicitly endorse these policy changes, she does suggest that the United States has no good options for preventing a Chinese assault on Taiwan, implying a false equivalence among the various approaches available to Washington. In reality, the risks are less imminent and more manageable than she suggests. The United States can maintain stability in the Taiwan Strait by bolstering Taiwan’s self-defense capabilities and adopting a lighter and more distributed—and thus less vulnerable—force posture in the Asia-Pacific. At the same time, Washington should strengthen its “one China” policy, reinforce strategic ambiguity, and refrain from making unconditional commitments to Taiwan.

Mastro rightly observes that if China were to take military action against Taiwan, it would have several options, ranging from an invasion to a blockade to the occupation of small offshore islands or strikes on selected economic or political targets. Although some of these options are more realistic than others, all would carry immense risk. Contrary to what Mastro suggests, Beijing is unlikely to attempt any of them unless it feels backed into a corner.

China’s most decisive option would be a cross-strait invasion. But its chances of succeeding today—and for the next decade at least—are poor. Moreover, failure would produce a wrecked fleet and an army of prisoners of war in Taiwan, an outcome that even Beijing would be unable to spin as a victory. If, as most China analysts believe, regime security is the top priority for Chinese leaders, an invasion would risk everything on dim prospects for glory.

To be sure, recent Chinese military modernization efforts have yielded potent new capabilities, and the People’s Liberation Army could visit havoc on Taiwan and US forces deployed in the region at the outset of a conflict. But the PLA still lacks the naval and air assets necessary to pull off a successful cross-strait attack. Just as important, it suffers from weaknesses in training, in the willingness or ability of junior officers to take initiative, and in the ability to coordinate ground, sea, and air forces in large, complex operations.

To put China’s naval capabilities in perspective, consider that the United States captured Okinawa in 1945 from a Japanese garrison that was roughly the size of Taiwan’s current active army with a fleet weighing 2.4 million tons and supported by 22 carriers, 18 battleships, and 29 cruisers. China’s amphibious fleet totals just 0.4 million tons today and would be supported by a much smaller fleet of combat ships that, unlike the battleships and cruisers of World War II, are not equipped with large guns capable of supporting troops ashore. China could supplement its naval transport vessels with civilian ships, but such ships unload slowly, as the British rediscovered in the Falklands in 1982, and these would share with the military fleet a limited number of landing craft for getting supplies from ship to shore. Chinese paratroopers or heliborne forces could also attempt to cross the strait, but they face even greater limitations and would be highly vulnerable to Taiwan’s surface-to-air missiles.

Even if China could triple the size of its amphibious transport fleet, its ships would remain vulnerable to counterattacks by the United States and Taiwan. To seize control of the island, China would need to keep its fleet off Taiwan’s coast for weeks, creating easy targets for antiship cruise missiles launched from Taiwan or from US bombers, fighter aircraft, and submarines. And even if the PLA managed to capture ports or airports, US bombers or submarines could put those facilities out of commission, assuming Taiwan’s forces did not sabotage them first. To be sure, China could strike US bases in Japan and threaten the US fleet operating east of Taiwan. But unless Taiwan were to collapse without a fight—a scenario on which leaders in Beijing are unlikely to gamble their own survival—China could not sustain a fleet off Taiwan’s beaches long enough to prevail.

Instead of an all-out invasion, China could opt for an air or sea blockade, seeking to starve Taiwan of trade until it capitulated to Beijing’s demands. But the potential upside would be smaller and less certain, and the potential downside almost as calamitous. A blockade would require China to operate aircraft and ships for extended periods of time to the east of Taiwan, once again creating targets for US bombers, aircraft, and submarines. As Mastro notes, China could respond by striking US bases in Japan, but doing so would ignite a broader war, with all the attendant risks China would have sought to avoid by stopping short of an invasion.

Mastro acknowledges that “China is unlikely to attack Taiwan unless it is confident that it can achieve a quick victory.” But blockades, by their nature, take months and sometimes years to yield results. Even a few months would give the United States sufficient time to mobilize its immense military might to break the blockade. And a blockade could be met not just with an attack on Chinese forces but also with a counterblockade of China. As a result, this option is also unlikely to deliver Taiwan into Chinese hands and, like an invasion, would succeed only if Taiwan essentially collapsed without a fight.

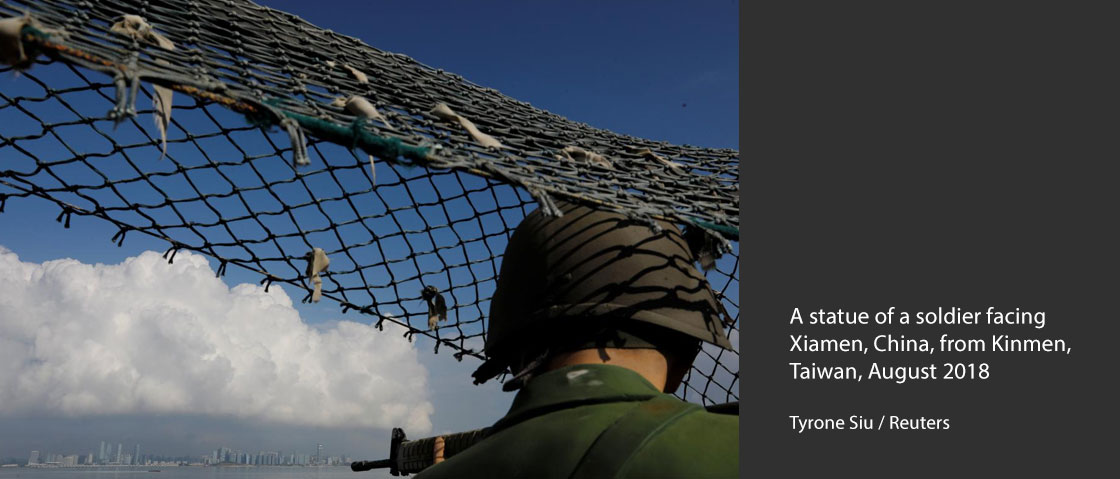

Less risky than an invasion or a full blockade would be more limited coercive actions. China could seize a small Taiwan-controlled island immediately off its mainland coast, for instance, or strike economic or political targets in Taiwan. Taiwan’s Kinmen Island is just five miles off the coast of the mainland, well within artillery range. Occupying the island is within China’s current military capability and would signal resolve but would not embroil Beijing in a larger conflict. If China seized Kinmen quickly and then ceased military operations, the onus would be on Taiwan—and the world—to respond or accept the fait accompli.

But Beijing is unlikely to undertake even limited military action merely because it can, as Mastro suggests it might. China has had the ability to take Taiwan’s closest offshore islands for decades, but it has refrained from doing so. Should it decide to seize one of these islands in the future, the assault would be not “part of a phased invasion,” as Mastro argues, but a statement of frustration with a perceived shift in the US or Taiwanese status quo. Beijing would likewise have to think long and hard before striking targets in Taiwan. Historically, coercive bombing campaigns have achieved limited success, and such attacks would expose China to considerable economic and political risk. Beijing cares about its international reputation, and although it may never forswear the use of force to achieve unification, it is not eager to attack Taiwan without a clear pretext and an endgame that serves its political purposes.

Instead of overreacting to Beijing’s growing power, Washington and Taipei should foster peace and stability through a more balanced set of military and political measures. On the military front, they should continue to deter Chinese aggression by implementing their own respective denial strategies, neither of which would require a major military buildup or the integration of US and Taiwanese forces. To that end, the United States should adopt a lighter military footprint in the western Pacific, one that is better able to withstand a Chinese attack and wear down Chinese naval and air forces should they attack Taiwan. It should invest in a distributed air and naval presence rather than in ground forces, more long-range antiship missiles and fewer weapons designed to strike deep into China, and light aircraft carriers to supplement a reduced force of large-deck carriers. Such adjustments would highlight the enormous risks to China of offensive military action and provide the United States with a more usable set of tools, ones that would not risk escalation in the event of a crisis.

Taiwan should also improve its own defenses. Under President Tsai Ing-wen, Taipei has adopted a more rational defense strategy that emphasizes resilience and sustainability. Washington should incentivize further movement in this direction by selling Taipei defensive weapons capable of surviving a Chinese assault, including antiship cruise missiles, smart mines, drones, and air defense systems, rather than the vulnerable aircraft and warships Taipei has preferred in the past. It should also condition such sales on Taiwan’s willingness to enhance the readiness and training of its troops, especially its reserve forces.

Washington needs the right political strategy to accompany these military efforts. As the pioneering game theorist Thomas Schelling observed, reassurance is an essential corollary to deterrence, because it presents potential adversaries with a real alternative to aggression. Washington should therefore refrain from further blurring the line between cultural and economic engagement with Taiwan and official political recognition, a distinction that lies at the heart of the agreements that accompanied the normalization of US-Chinese diplomatic relations. It should also make clear that it remains committed to the “one China” policy by explicitly reaffirming that it does not favor a unilateral assertion of Taiwanese independence and that it supports the peaceful resolution of cross-strait differences.

At the same time, the United States should pursue bilateral cooperation with China on issues such as climate change and pandemic management. It should also open an official nuclear dialogue with China and invest in improving military and civilian crisis communication channels, including negotiating procedures for coast guard vessel encounters. In private, US President Joe Biden should emphasize to Chinese President Xi Jinping that the main obstacle to unification is not the US military or the relationship between the United States and Taiwan but China’s own failure to develop a viable peaceful unification strategy that appeals to the people of Taiwan.

Because Beijing refuses to engage the moderate Tsai administration, these measures are unlikely to improve cross-strait relations anytime soon. But by playing a long game of balanced deterrence and reassurance, the United States can discourage Chinese adventurism even as it leaves the door open to positive change.

RACHEL ESPLIN ODELL is a Research Fellow in the East Asia Program at the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft.

ERIC HEGINBOTHAM is Principal Research Scientist at the Center for International Studies at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.