The Great War was a wellspring of the great horrors and tragedies of the 20th century, says the Ford International Professor of Political Science.

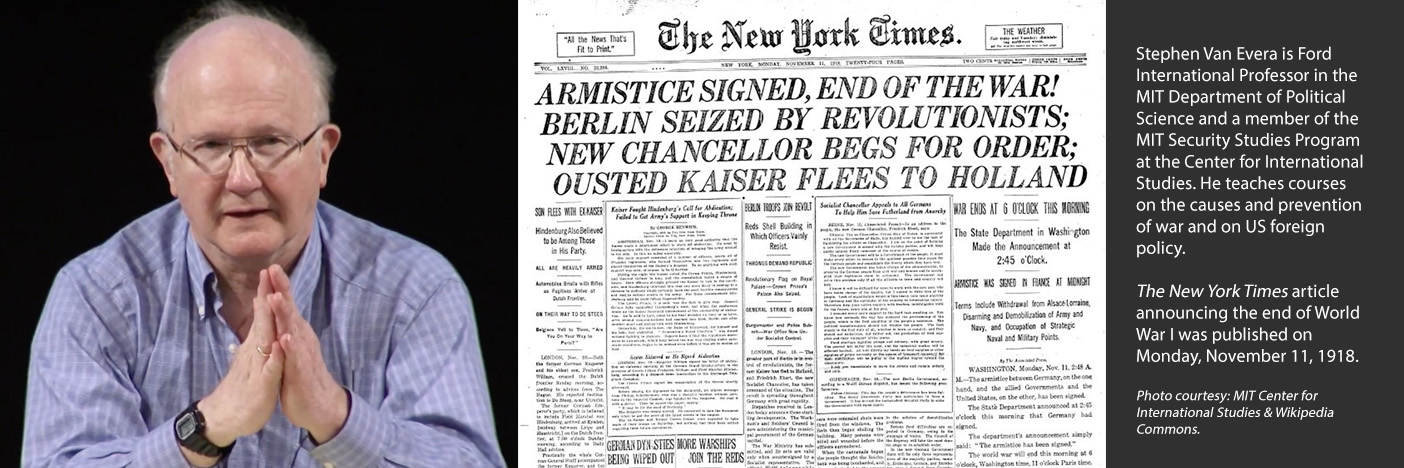

One hundred years ago on November 11, 1918, the Allied Powers and Germany signed an armistice bringing to an end World War I. That bloody conflict decimated Europe and destroyed three major empires (Austrian, Russian, and Ottoman). Its aftershocks still echo in our own times.

As we approach this day of remembrance—commemorated throughout Europe as Armistice Day, and in the US as Veteran’s Day—it is a reminder of Machiavelli's tenet that ‘‘whoever wishes to foresee the future must consult the past."

Stephen Van Evera, Ford International Professor of Political Science and an expert on the causes of war, revisits the Great War and discusses key insights for today one century after its bitter end.

ME: Who caused the war? Do historians agree or not? Where does the debate stand?

SVE: My answer: the Germans caused the war. They wanted a general European war in 1914 and deliberately brought it about. Their deed was the crime of the century.

But others disagree. A hundred years later scholars still dispute which state was most responsible. Views have evolved a lot but there is no consensus.

During 1919-45 most German historians blamed Russia, or Britain, or France, while deeming Germany largely innocent. Historians outside Germany generally viewed the war as an accident, for which all the European powers deserved blame. Few put primary responsibility on Germany.

Then in 1961 and 1969 German historian Fritz Fischer published books that put greatest blame on Germany. His books stirred one of the most intense historical debates we've ever seen. The firestorm was covered in the German popular press, debated at public forums attended by thousands, and discussed in the German parliament, as though the soul of Germany was at stake—which in a way it was. Fischer and most Fischer followers argued that Germany instigated the 1914 July crisis in order to ignite a local Balkan war that would improve Germany’s power position in Europe. German leaders did not want a general European war, but they deliberately risked such a war, and lost control of events. Some Fischerites went further, arguing that Germany instigated the 1914 July crisis in order to cause a general European war, which they wanted for “preventive” reasons—they hoped to cut Russian power down to size before Russia’s military power outgrew German power—and to position Germany to seize a wider empire in Europe and Africa. Both Fischer variants assign Germany prime responsibility.

The Fischer school offered strong support for their argument, and new evidence discovered since Fischer wrote further corroborates their view. For example, John Röhl recently found evidence of a German-Austrian meeting in November 1912 where a joint move toward general war was apparently agreed. (See John Röhl, Into the Abyss [2014], pp. 889-911.) Germany was making nasty plans! We have also learned that after 1914 German leaders privately confessed their responsibility for the war. In 1915 German general Helmut von Moltke, who had large influence on German policy in 1914, complained from retirement that “it is dreadful to be condemned to inactivity in this war which I prepared and initiated.” German Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg confessed in 1917 that “yes, it was in a sense a preventive war.” His foreign secretary Gottlieb von Jagow privately admitted in 1918 that “Germany wanted the war” that by then had gone disastrously wrong. These are telltale statements.

Within Germany the Fischer view holds sway today. Germans broadly take responsibility for the war. But several recent works by non-Germans reject the Fischer view, assigning Germany less responsibility than Fischer while blaming others more. Sean McMeekin blames Russia more than Germany. Christopher Clark blames all the major powers, without putting particular blame on Germany. Marc Trachtenberg argues that the Fischer school blames Germany unduly. So the Fischer school's views predominate in Germany but elsewhere the debate continues.

ME: What caused the war? That is, what phenomena?

SVE: The prime cause of the war was German aggression. The prime cause of German aggression was German militarism, i.e., the undue influence of the German military over German civilian perceptions of foreign policy and national security. The Wilhelmine German army had great domestic power and prestige. It used this power and prestige to infuse German society with a Darwinistic vision of world politics and a rose-colored view of warfare. Its propagandists told Germans that the life of states is nasty, brutish, and short; that states must conquer or be conquered; that states must strike others when the time is ripe or later be destroyed; that states must grow or die. As a result, German militarists argued, war was often necessary. They also claimed that wars usually ended quickly, before doing much damage, and warfare was a positive and even glorious experience. Hence, they argued, force was both necessary and cheap to use. These visions were illusions—the fake news of the time—but Germans widely believed them. As a result Germans civilians favored the bellicose policies that Germany pursued in 1914.

ME: Why is it important for scholars to assign responsibility for World War I, or for other wars?

SVE: When responsibility for past war is left unassigned, chauvinist mythmakers on one or both sides will over-blame the other for causing the war while whitewashing their own responsibility. Both sides will then be angered when the other refuses to admit responsibility and apologize for violence they believe the other caused, and be further angered that the other has the gall to blame them for this violence. They may also infer that the other may resort to violence again, as its non-apology shows that it sees nothing wrong with its past violence.

The German government infused German society with self-whitewashing, other-maligning myths of this kind about World War I origins during the interwar years. These myths played a key role in fueling Hitler’s rise to power in Germany in 1933. They were devised and spread by the Kriegsschuldreferat (War Guilt Office), a secret unit in the German foreign ministry. The Kriegsschuldreferat sponsored twisted accounts of the war’s origins by nationalist German historians, underwrote mass propaganda on the war’s origins, selectively edited document collections, and worked to corrupt historical understanding abroad by exporting this propaganda to Britain, France, and the US. This innocence propaganda persuaded the German public that Germany had little or no responsibility for causing the war. Germans were taught instead that Britain instigated the war; then outrageously blamed Germany for the war in the Versailles treaty’s “War Guilt” clause; and then forced Germany to pay reparations for a war Britain itself began.

An enraging narrative for Germans who believed it! And many Germans did. Hitler's rise to power was fueled in part by the wave of German public fear and fury that this false narrative fostered. Hitler told Germans that Germany’s neighbors had attacked Germany in 1914 without reason, and then falsely denied their crime while falsely blaming Germany in the Versailles Treaty. This injustice had to be redressed.

After 1945 international politics in Western Europe was miraculously transformed. War became unthinkable in a region where rivers of blood had flowed for centuries. This political transformation stemmed in important part from a transformation in the teaching of international history in European schools and universities. The international history of Europe was commonized. Europeans everywhere now learned largely the same history instead of imbibing their own national myths. An important cause of war, chauvinist nationalist mythmaking, was erased. Greatest credit for this achievement goes to truthtelling German historians and school teachers who documented German responsibility for World War I, World War II and the Holocaust and taught it to the German people. By enabling a rough consensus among former belligerents on who was responsible for past violence these historians—including the Fischerites and also others—and school teachers played a large role in healing the wounds of the world wars and making another round of war impossible.

An amazing turnabout! After wallowing in lies from 1918 until the 1960s, Germany has set the gold standard for truthtelling about the national past. Germans have a very difficult past to confront, and have confronted it in outstanding fashion. This German truthtelling project sets an example for all to follow. Honors are due those who inspired it and carried it out. Germany’s truthtelling historians and school teachers top the list of those who merit a yet-ungiven Nobel peace prize. Memo to Nobel awards committee: seek ways to correct this oversight!

Nationalist/chauvinist historical mythmaking declined worldwide after World War II but it never disappeared. It still infects many places. Contemporary Turkish chauvinism is fed by Turkish denial of incontrovertible Turkish responsibility for the 1915 genocide of the Armenian people. With rare exceptions (eg, Saburo Ienaga) Japanese leaders and historians still avoid offering a forthright and unqualified admission of Japan’s aggressions and crimes in World War II. Admirable exceptions aside (eg, the Israeli “new historians”) Arabs and Israelis both repeat self-whitewashing, other-blackening narratives about one another. These narratives feed fear and hatred on both sides. The worldwide Christian community remains largely unaware of the scope of past Christian crimes against the Jewish people, and of past aggressions against the Muslim world. This inhibits Christians from moving to heal the wounds their churches and communities inflicted in the past. The Sunni Muslim world is likewise unaware of the great violence committed by Sunni Muslims against others, including Christians, Shia Muslims, Ahmadis, Yazidis, and other non-Sunnis in South Sudan, East Timor, Armenia, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Yemen, Iraq, Syria, Indonesia, and elsewhere. This ignorance fuels Sunnis’ sense of victimhood, which in turn feeds Sunni extremism, manifest in the violence of Al Qaeda, ISIS, and affiliates.

Within the US the white South clings to a false account of the origins of the civil war ("It wasn't about slavery") and the nature of slavery ("It wasn't so bad."). This innocence narrative feeds a white sense of victimhood, which in turn fuels white southern hostility to enforcing equal rights for all Americans and white southern support for extremists like those who chanted “Jews will not replace us” and murdered Heather Heyer in Charlottesville in 2017.

These communities should learn from Germany’s example. If, like Germany, they faced their past truthfully they would downsize their sense of victimhood to better fit the facts. Their sense of grievance and entitlement would diminish accordingly. They would be quicker to see the justice in others' claims and to grant what others deserve. Peace with their neighbors would be easier to reach and sustain. War would be easier to avoid.

ME: What consequences (past and present) arose from the impact of the Great War?

SVE: Like a boulder that triggers a landslide as it tumbles downhill, World War I unleashed forces that later caused even greater violence.

Without World War I there would have been no Hitler, as he rose to power on (trumped up) grievances that stemmed from World War I, as discussed above. Hence without World War I there would have been no World War II. There also would have been no Holocaust, as the Holocaust was a particular project of the Nazi elite that other German elites would not have pursued had they ruled instead of Hitler.

Without World War I there would have been no Russian revolution; hence no Leninism or Stalinism; hence no vast massacres by Stalin (~30 million murdered); and no Cold War between the Soviet Union and the West during 1947-89; hence no peripheral wars in Korea, Indochina, Afghanistan, Angola, Nicaragua, El Salvador, and Cambodia, killing millions. There would have been no CIA coups in Guatemala, Congo, and perhaps Indonesia, hence no ensuing civil wars and/or massacres in these countries, killing many hundreds of thousands. There would have been no communist takeovers in China, Yugoslavia, Cambodia or North Korea, hence no epic communist-engineered massacres or famines in those lands (over 30 million were killed or died of famine born of crazed social engineering in China alone).

Moral of story: war can be self-feeding, self-perpetuating and self-expanding. It has fire-like properties that cause it to continue once it begins. It is hard to extinguish because, like fire, it sustains itself by generating its own heat. In this case the “heat” is mutual fear and mutual hatred born of wartime violence, and war-generated combat political ideologies, like Bolshevism, Naziism, and extremist Sunni jihadism, that see human affairs as a Darwinistic struggle that compels groups to destroy others or be destroyed themselves. Implication: preventing war of all kinds should take high priority. War can reach out and touch even those who are far away at the outset, or are yet unborn. Its furies cannot be predicted and sometimes cannot be contained. We should address these furies by moving to prevent war before it begins.