MICHELLE ENGLISH: Before we get started, I'd like to mention that we have at least two more Star Forums happening this spring. On April 23rd we will be hosting an event called 70 Years Israel Palestine, Reflections and Forecasts. The participating panelists will be announced soon.

And on May 3rd, Mexico's current secretary of foreign affairs, who received his PhD from MIT, will be giving a talk on US Mexico relations. We have details about these talks at our table, and also a place where you can sign up to get on our email list if you want to hear about other events.

A reminder that our talk will conclude with a Q&A with the audience, and just to line up behind the mic so that we can hear you. We are video, making a video of this talk. And also a reminder to ask one question. Now I'd like to introduce our speakers.

A reminder that our talk will conclude with a Q&A with the audience, and just to line up behind the mic so that we can hear you. We are video, making a video of this talk. And also a reminder to ask one question. Now I'd like to introduce our speakers.

We have Nimmi Gowrinathan, who is, is this OK? Keep going? OK. Who is the founding director of the Politics of Sexual Violence Initiative, which examines the impact of rape on women's political identities. She's a visiting research professor at the Colin Powell School for Civic and Global Leadership at the City College of New York. And through this initiative, she is the director of Beyond Identity, a gendered platform for scholar activists.

She's also currently a senior scholar for the Center for Political Conflict, Gender and People's Rights at the University of California-Berkeley, and the creator of the Female Fighter series at Guernica magazine. She provides expert analysis for CNN, MSNBC, Al Jazeera and the BBC. And is published in Harper's Magazine, Foreign Affairs, Guernica magazine and Al Jazeera English, among others.

We also have with us today, Kate Cronin-Furman. She's a human rights lawyer and political scientist who works on post-conflict environments. Her research addresses human rights outcomes after political violence, accountability for mass atrocities, and international intervention.

Her research has been published and is also forthcoming in International Studies Quarterly, Political Science and Politics and the International Journal of Transitional Justice. She also writes regularly for the mainstream media, with recent commentary pieces appearing in Slate, Foreign Policy, the Washington Post's Monkey Cage blog, War on the Rocks and Al Jazeera.

Kate is currently a post-doctoral research fellow in the International Security program at Harvard Kennedy School's Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. Please join me in welcoming our speakers.

[APPLAUSE]

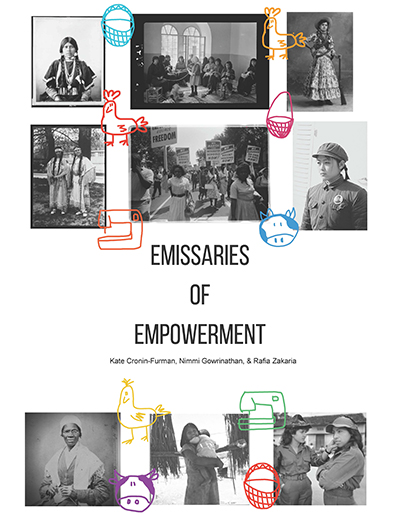

NIMMI GOWRINATHAN: Hi, thank you for having us. I don't know how many of you have gotten to see the paper, “Emissaries of Empowerment,” but it's up online if you want a copy afterwards. But this is most of what we'll be talking about today. So for much of my career, which was in the policy world, human rights research and the academy, I felt like I was an entry point for Westerners into the Tamil community in Sri Lanka. I'm Tamil Sri Lankan. And specifically into Tamil women. It was only much later that I started to see social justice issues as they were framed in the Western context from the perspective of Tamil women. And I began to center that analysis instead. And this paper really emerged from that thinking, from trying to reverse the lens of analysis.

NIMMI GOWRINATHAN: Hi, thank you for having us. I don't know how many of you have gotten to see the paper, “Emissaries of Empowerment,” but it's up online if you want a copy afterwards. But this is most of what we'll be talking about today. So for much of my career, which was in the policy world, human rights research and the academy, I felt like I was an entry point for Westerners into the Tamil community in Sri Lanka. I'm Tamil Sri Lankan. And specifically into Tamil women. It was only much later that I started to see social justice issues as they were framed in the Western context from the perspective of Tamil women. And I began to center that analysis instead. And this paper really emerged from that thinking, from trying to reverse the lens of analysis.

The paper is called “Emissaries of Empowerment.” Power for women is universally difficult access. And in the development world, the attempt to remedy this has been through the use of the empowerment programming. The literal definition of this is the transfer of power from those with power to the powerless.

And the word itself has been broad enough to capture everything from the mission statement of Save the Children to the work of ISIS. So the word has been diluted to the point of almost complete ambiguity now. Today this word is sort of omnipresent in the West, particularly when it comes to the donors and donor programming around gender.

The paper examines though the roots of this word, the origins of this word. The term was originally introduced to development sphere when a group of feminists from the Global South met in the 1970s in South India. Among these women were a reproductive rights expert who founded the first women's center in Brazil, a pioneering anthropologist from Mexico, an activist for Dalits rights in India.

And these women came together for a conversation about collective change. So when they met, they were intimately familiar with the conditions of women's oppression. And they centered their conversation on the political forces responsible for that. They emerged from a history of women in each of their countries that were armed, that were active, that were enraged, and who were fighting for power.

And this is important. They were fighting against colonial interests and cultural repression at the same time. For them, the term empowerment was the foundation of an explicitly political project. It was intended to incite a kind of collective mobilization around the political issues, the structural issues that we're keeping women of color in a particular place.

So now we have nearly 50 years later, empowerment programming in the Global South, which ranges from impoverished indigenous women in Bolivia stitching string bikinis for white women to shop with a purpose, to ex-combatants in Sri Lanka being offered training in icing cakes and hairstyling and sewing classes. So what we're looking for is, how did this happen? How did this transition happen?

So now we have nearly 50 years later, empowerment programming in the Global South, which ranges from impoverished indigenous women in Bolivia stitching string bikinis for white women to shop with a purpose, to ex-combatants in Sri Lanka being offered training in icing cakes and hairstyling and sewing classes. So what we're looking for is, how did this happen? How did this transition happen?

So as both a disaster aid worker and a scholar, researching the motivations of female fighters in conflict zones, my work over the years has continually revealed an inability to acknowledge the distinctive politics of women. And I say distinctive politics, because this has to include the politics that we don't agree with. And this has been, in my opinion, the failure of a number of our interventions.

So I have spent years actually handing out cows and chickens to women who were raped. Speaking to former combatants about the beauty school programming that they're in. And really, allocating sewing machines to any woman anywhere who suffered any kind of trauma.

So what started in the Global South as a political project, we find now to be the sort of linchpin of anti-politics. What we're trying to get at here is the underlying feminist ideology that's driving this kind of programming. What are its roots? And most importantly, what are the political structures that are keeping this in place? Why do we still have this over and over and over again? Why do we have every program with women have a reference to the question of empowerment?

And the question of power and politics, as this word entered the sort of lexicon of the United Nations and other international bodies, what was this tool for the powerless to challenge the structures of political inequality, became this limited technical solution to issues of education, of poverty, of health care. So for women in particular, this programming carefully and calculatedly delinks power from politics.

Much of this began with the construction of the victim, and I'll leave that to my colleague to discuss further. This construction of the victim though, it's important to note, we trace the narrative, the image of her, this victimized woman in the developing world, back to the colonial period. Back to the time when white women in colonial countries were asked to intervene, were called to intervene to save uncivilized women.

And this sounds like it's a little bit of a stretch, but the research actually found something very fascinating. There were publications like The Englishwoman's Review, which were for the wives of the colonial interveners, who classified native women in the colonies such as India, as special and deserving objects of feminist concern.

In the Democratic Republic of Congo, the contemporary iterations of this approach can be found in the media adulation of a white woman's journey through the heart of darkness. You know, in the constant imagery of the sexualized, brutalized Congolese women. So this approach of defining an individual, defining a woman through her trauma has two key purposes.

It allows the interveners and interventions to operate purely on a moral obligation to intervene, thereby shutting down any political conversation that emerges after that. And a victim who is sexualized is almost never a political actor. So when you see it constantly over and over again, the sexualized image of a woman, nobody expects political action from this woman. Nobody looks for the politics in this woman.

There is, for us, one of the things that we examine is this question of culture. Now I found over and over again through policy work, through academic work, I usually get asked the question about culture. And what I found is that culture becomes this really useful perpetrator. One can blame it for everything, and nobody is held accountable. Once it's culture, there's nothing that can be done about it.

And this is a culture that's meant to be a culture that is static, a culture that doesn't shift, one that one assumes is just inherent to a particular land or a particular people or a particular religion. And when I get asked this question often, you know, what about the role of culture, I'll always ask, which culture are you talking about?

Because there are certain cultures with the UN, the key to transformative change is to deal with culture. The culture that you're talking about is the one that the UN has no control over. The UN has no ability to intervene into that space. What you can intervene on, is a culture of violence, a culture of dependency, a culture of militarization.

Those are the things that external actors can engage with. But culture becomes very useful. And again in the interventions for women, what's highlighted is the evils of local cultures, which is again, reinforces the idea of the moral duty. Agency, the question of women's agency, which comes up a lot in academic and in development language, is only seen when the woman is acting in opposition to her culture.

Her agency was measured when she challenges her own culture, not when she challenges the political spaces that she is a part of. So we argue that this sort of limited approach to agency actually circumscribes women and takes away any ability at political action for them.

One of the things that we want to distinguish is this question of NGO-ization versus do depoliticization. A lot of this critique has been made in the world, in the conversation around the NGO-ization. Arundhati Roy and others have talked about the role of NGOs and handing out by benevolence what ought to be somebody's by right.

One of the things that we want to distinguish is this question of NGO-ization versus do depoliticization. A lot of this critique has been made in the world, in the conversation around the NGO-ization. Arundhati Roy and others have talked about the role of NGOs and handing out by benevolence what ought to be somebody's by right.

The distinction that we're making here is that the argument NGO-ization is largely that the state has retreated, the state has given up, the state has left this population behind and the NGOs come in. And the NGOs are in that place, shaping political movements in donor-driven terms, which is a legitimate argument.

What we're saying is that the distance between the marginalized women and the state, their access to levers of power is so vast, the NGOs step in between these two spaces. And in the positioning that they occupy, they actually reinforce what the state wants. Which is to say that the state didn't just retreat, the state didn't just give up, the state didn't just leave populations behind.

There's a reason why populations are kept in the position that they are. And when NGOs enter with the position that they have, and they do these empowerment programs, they reinforce this. They actually reinforce the repression of women politically, which is what the state wants.

This is not just NGOs. Kate and I have an earlier report called. "The Forever Victims." There's a number of actors that do this in that space. "The Forever Victims" looks at sexual violence in Sri Lanka and it doesn't recount the number of sexual violence cases or who did it.

What it does is, it examines how sexual violence is used politically by everybody to obtain a certain political agenda. How it's used by local politicians. How it's used by the state. How it's used by NGOs. How is sexual violence as an issue, used politically by everybody, rather than the numbers.

My work now is on the role of rage in politics. It's on reclaiming rage. In this particular environment, I believe that rage sustains a struggle that hope might leave behind. In Canada this year, I was with a population of Tamil refugees, Tamil women, who said themselves that they had no illusion that either society was built for them. Tamil society or society in Canada.

They expected to exist in a space where they were dependent on support, where they were dependent on NGOs. They already expected that. But more than three of these women say they're exhausted and enraged from navigating the system of support in itself.

They expected to exist in a space where they were dependent on support, where they were dependent on NGOs. They already expected that. But more than three of these women say they're exhausted and enraged from navigating the system of support in itself.

This approach, this depoliticizing contributes to the kind of rage that marginalized women are likely to feel. The problem with this, with examining rage, rage is a space that I believe women are forced to inhabit. It's more emotively driven than anger, more intellectually tempered than insanity.

Rage is a place from which the most productive politics can emerge. But as with most hard labor, most women who have earned the right to rage, do not feel entitled to it. What do these interventions do to rage? How do they sublimate them? How do they shift them? How do they take away their ability to produce politics?

For me, my research is on female fighters. And the radical violent female fighter is the extreme that reveals the rage in the everyday. The rape that pushes her away from society. The marriage that traps her within it. The military occupation that intrudes on every movement. And, and this is important, and the apparatus that tries to save her from it all. All four of these are contributing to the female fighter and her existence.

So I'll just talk a little bit about the female fighter. You know, as we've sort of presented this work, and I present in my own work on female fighters, there is something about women as entrepreneurs of violence that makes people deeply uncomfortable. It's not something that they're ready to address in the policy world and activist spaces.

And the female fighter has a very uncomfortable positioning in aid complex. She's neither a victim to be saved, nor an agent to be fully supported. To me, she offers as a way of understanding, a new way of supporting politics. And I think when you examine these highly politicized women, most of the women I work with were highly politicized, were combatants in movements, were front line fighters, were captains of various battles.

You're able to see in the post-conflict period, when they've been demobilized, how far apart these interventions are. How depoliticizing this is when we have ex-combatants who they're offered beauty salons. So the ex-combatant has essentially become the latest sort of labeled identity in the developing world.

Rape victim, widow, beneficiary, all the other labels that we give to women based on trauma. The ex-combatant is now is now one of these categories. The ex-combatants in Sri Lanka have told me over and over again, we have no use for sewing. I have no use for this course, but when I finish my sewing course, the government considers me deradicalized.

Just a month ago I was with one of the women in the FARC who I've met with a few times, and she told me, she was a senior FARC member in Colombia, and she told me right when the war ended, everybody came in with interventions, with offers to help.

And I didn't even ask her before she said, they came in with all these sewing machines. She said, I told them back then, no, I don't want it. This is not what we want. And I met with her now a year later, a month ago, and she said she's really afraid, because she feels that this is the only option for politicized women in FARC.

And you see this interesting divide now happening in Colombia, where almost half of the female combatants have not given up their arms, have refused to give up their arms. The other half, she says she fears, have lost their politics. They've given into whatever option the INGOs are bringing in. Sewing machines and cakes and bakeries and all of that. So this is the approach that we're trying to challenge here.

I'll just end by saying that this is, it's a difficult conversation. We've been talking about this in different spaces for about a year now. And one thing I want to be clear about is that this is not a racially divisive question. It is not a question of a white, third world feminist divide.

But in some ways, it feels like much of engagement between first and third what feminists, has been done in the development sphere. So if we can begin here, it feels like a good place to find a connection. This is a question of an approach. I think in itself, a testament to the desire to have pragmatism over politics and simple solutions over a complex conversation.

The question we get asked most of the time, I get asked all the time, so, what is the solution? What are your recommendations? Again, it's really this desire to constantly have a quick fix to something. My issue with this is, that there's not been an acknowledgment of the problem. It feels like everyone's skipping a step. OK, I heard what you said, how do we get to a solution? But the problem is an uncomfortable conversation.

It in the development industry, requires that there's a dismantling of this guise of empowerment, in order to reveal funding, incentives, colonial legacies, and political agendas with existing gender perceptions that overlay all of that, to the design of empowerment programming. Once we have that conversation, we can get to the other side of it. But what we're finding is that people are not willing to sit with this, which is the problem.

KATE CRONIN-FURMAN: So we begin this report with an anecdote of mine. I was in Cambodia a few years ago, where I had actually lived for a while previously. And I was at dinner with colleagues who worked at various NGOs in the capital city.

KATE CRONIN-FURMAN: So we begin this report with an anecdote of mine. I was in Cambodia a few years ago, where I had actually lived for a while previously. And I was at dinner with colleagues who worked at various NGOs in the capital city.

And one of the women, we were having drinks and kind of venting about our days, one of the women told us this story about a meeting that she had had that day with the representative of one of their Western donors that was supporting their work. She was working for an anti-trafficking organization, and this was a big Scandinavian funder that was supporting the work.

And the donor had sent a film crew to Cambodia to catch a video of the good that their money was doing. And so they wanted to film a beneficiary, which means they wanted to film a trafficking victim. And the workers at the NGO were a little uncomfortable with this.

But ultimately said, OK, we have this woman who is a former trafficking victim who's spoken publicly about what happened to her, and she's willing to go on camera. And so they brought the film crew to meet her. And the film crew said, no, this is not the image we want. The woman was 22 years old. She didn't look like a teenager. She was happily nursing a young child.

She didn't look traumatized. This was not what they were looking for in their movie. And as we started to draft this report and sent it around a friends, multiple people picked up on this anecdote and said, oh my god, the same thing happened to me, but in Congo or in Liberia.

A donor came in, wanted the youngest, the most traumatized, the most sexualized, the most vulnerable victim to film. And with these anecdotes underscore is something that all of us who work in this industry know, which is that victimization sells. To draw interest and therefore press coverage and funding to your cause, you want again, the youngest, the most traumatized, the most sexualized victim you can find.

And as we note in the report, although this is fairly widely known and kind of discussed over beers, what's less frequently acknowledged is that this fact is actually a design feature. It's not a bug of the humanitarian and development aid industries. And this is especially true as it relates to interventions to improve the lives of women.

So unfortunately, what this means is that the portrayals of victims that are propagated by those who are supposedly helping them, tend to be degrading, dehumanizing and profoundly exploitative. So as Nimmi mentioned, one of the examples that we use in the report is the way in which women who have been raped during the conflict in eastern Congo are framed by Western media.

The stories that are told about them again, by those who are trying to help them, are incredibly sensationalistic and voyeuristic. And what we see in the Western media coverage of this crisis has been a sort of one-upmanship, to give the most gory, most graphic details.

It's very common to see news stories that invoke rape with weapons, with guns. It's common to see elements of cannibalism, and other particularly sadistic forms of sexual torture. And in the process of reporting these stories, we learn almost nothing about these women, except that they were brutally raped.

So in this report, we are talking about the ways in which some of these dynamics are both produced and entrenched by the Western white feminist gaze. And we highlight the ways in which press coverage of places like Congo, center white women interveners into the lives of women in the developing world.

While the beneficiaries of the interventions, the brown and black women, are stripped of their subjecthood and presented in this very one-dimensional, very fetishized way. And we connect this to the kind of depoliticization that Nimmi has just discussed. This is a failure to take non-Western women seriously as subjects. And we trace that to the days of colonial interventions.

Our co-author, who's unfortunately not here with us, Rafia, did some really fascinating research into the deep history of this stuff. And kind of the rhetoric of Indian women as passive vessels for the feminism of British women, and the kind of early origins of the concept of saving brown women from brown men.

So we see this tendency to center Western women rather than marginalized women that sort of favor the abandonment of complex narratives in favor of these simple stories. In, for instance, the reporting of Nicholas Kristof in The New York Times. His coverage in particular of the Congo, has often focused on these white women, who become aware of the suffering of their Congolese sisters, undergo an epiphany and uproot their lives to go and help.

And these stories have really familiar arc and characteristics. We have a white woman who becomes enlightened, who learns and grows. We have extremely graphic descriptions of the injuries inflicted on non-white women. We have no additional details about these non-white women. It's always about the audience, it's not about the people who are being seen.

And I'm not just picking on Nic Kristof here. I am, a little, but this isn't an academic quibble. There are actually practical consequences to the narratives that we tell about victims. So if we treat them as object, as stripped of all agency, we are comfortable with interventions that are based on interveners' judgment about what they need.

And we see this tendency reinforced by the production of success stories, which is also something that hearkens back to colonial interventions. We have this great story in the report about this woman named Rukhmabai? Is that it? Who is rescued by a white Christian woman from a child marriage. She's empowered to go on to study, and she's trotted around to be shown off as the success of intervention.

She's been helped by Westerners to resist her culture and she's gone on to great things. And these kind of stories, which we very much still see today in these tales of white women who have gone to the Congo to empower and rescue Congolese women, this stories become the justification for further activism in this vein. So this is a self-reinforcing cycle.

And the upshot is that we get interventions that kind of run the gamut from goofy to sort of horrifying. And in the report we talk about a few of them. Specifically in Congo, one of my favorite examples to cite, is when Hillary Clinton as Secretary of State went to Goma in I'm going to say 2009, promised a lot of funding to help women who had been raped during the conflict there.

And one of the big initiatives that they announced was that they were going to be supplying video cameras to rape victims. That's like OK, let's parse this out a little bit. These women have already been raped. So not sure what they're filming. The electrical grid is terrible, so not sure how they're going to recharge these cameras. And this is a context of profound instability.

So the likelihood that they might get mugged and robbed of these cameras is pretty high. There was basically no theory of change in place other than that, hey, we like to fund tech. Hey, we want to help rape victims. Let's give them cameras. And I suspect, if anyone had talked to them seriously about what their needs were, they might have come up with a slightly different intervention.

So that's my example that's on the more goofy end of the spectrum. Another example that I frequently cite I find a bit more disturbing. And that's the work of an organization in Sierra Leone that was essentially crowdsourcing funds for fistula repair for women who had been injured during childbirth.

And the way that they went about this was to put up a website with pictures of these women with their names, and with the most graphic descriptions of their fistulas. Which sure, I'm sure that these women did indeed consent to this, because the prospect of having this very devastating and stigmatizing injury repaired was a huge incentive.

But could you imagine having to disclose the very personal details of your gynecological injury to the internet at large, in order to benefit from assistance to have it medically treated? So these are the kind of things that we observe as the results of these types of narratives that are very much failing to center the agency of the women that they're trying to help. And obviously, these dynamics are not limited to the field of women's empowerment. And I'm going to talk a little bit about my broader research into mass atrocities and that kind of sector of issues.

But could you imagine having to disclose the very personal details of your gynecological injury to the internet at large, in order to benefit from assistance to have it medically treated? So these are the kind of things that we observe as the results of these types of narratives that are very much failing to center the agency of the women that they're trying to help. And obviously, these dynamics are not limited to the field of women's empowerment. And I'm going to talk a little bit about my broader research into mass atrocities and that kind of sector of issues.

Because we see this, if you think about the issues, the images that are used in humanitarian appeals, for instance, I'm sure you've all seen the images of babies with the swollen bellies, with the flies on them, the dead-eyed young women trying to a child and failing to produce milk.

This is imagery that is chosen not for what it does to the victim, but for the response that it evokes in the audience. And one of the examples that I love to teach in my college classes of this, is the Kony 2012 video. And for those who don't remember, this was this viral video. It was the first example of clicktivism blowing up.

This is the group Invisible Children, advocating for US military intervention to save the victims of Uganda's rebel group, the Lord's Resistance Army. And it's a really particularly egregious example of the sorts of things that I'm talking about here. It's got your one-dimensional victim portrayal, your centering of heroic Western interveners.

It's a little indifferent to the details of what's actually going on and in which country. And it offers a very problematic policy prescription as a result of these things. So their answer to the problem is essentially the application of American military force. Which by the way, did get put in place and did not do what they wanted it to do. Joseph Kony is still at large.

So I like to pick on Invisible Children, as I like to pick on Kristof, but these kind of narratives are really common throughout the field of post-conflict response, throughout the field of atrocity response. And that's in part, because these are fields where the concept of the victim looms very large.

Calls for intervention, calls for accountability, are generally grounded in the rights and needs of the victim. So we get a lot of references to the voice of the victim. But when we hear that voice, it's almost always been packaged by an intermediary in the service of some goal.

So people's stories are being used to advance a purpose that is not their own. It's selling newspapers for journalists, it's justifying a particular policy response for advocates. And the ability to do this, to package their stories in this way, is facilitated by a common feature of violent contacts, of developing contacts. And that's the incredible ease for outsiders of accessing vulnerable and traumatized populations.

This would never be possible in the West. We have regulations that prevent you from rocking up to a hospital and interviewing child victims of sexual assault. We have professional ethics that guard against that. But in the developing world, especially in places that have experienced violence, we find victims telling and retelling their stories to domestic civil society, to journalists, to international advocates and to researchers.

We see masters and law students from around the world with no training in speaking to vulnerable populations, coming to interview the victims of serious human rights violations. And for my money, this is just profoundly unethical and problematic. And the reason it hooks into what we're talking about in this report, is that the pretense of being there to help conceals the extractive nature of these interactions.

All of these interlocutors occupy a position of privilege relative to these victims. And one of the takeaways of our report, is that it is not enough to want to help. Intervention, no matter how good intentioned, can be just as damaging as allowing the status quo to persist.

And that's especially true when interventions arise out of the idea that victims are in such dire straits, that anything we do for them is better than nothing. And that's where you get these aid interventions and advocacy platforms that strip people of their subjecthood and reduce them to the circumstances of the injuries that they've suffered.

And I do want to note here, that there's actually very strong incentives for victims to participate in their own reduction. So we very often see hierarchies of victimhood in place. States will validate certain kinds of experiences of harm. For instance, you might be able to get redress for crimes that were committed by a rebel force, but not by state forces.

And advocacy and aid does the same thing in a less overtly sinister way, by prioritizing certain types of violations. So we have numerous reports of women in Congo and Liberia and Sierra Leone identifying as rape victims, even if, in fact, they have not been the victims of sexual violence.

Because that provides them access to services that they would not have if they were just, for instance, the victims of torture. So we get these very complex questions about what kinds of suffering provide access to resources and status? And the result is that the complexity of victimhood gets collapsed.

Not just her community, but actually for individuals who may be the victims of multiple harms and may relate to their victimhood in ways that get erased. So what we see is that certain kinds of victimization become definitional. And there are incentive structures in place that compel certain kinds of performances of victimhood.

And that can be profoundly silencing to those who don't see themselves as included or represented. For instance, male victims of sexual violence are a really classic example of this. They are rarely being empowered by aid interventions. OK, so if this recognition of victimhood confers this certain kind of status on certain types of victims, it also confers power and status on other actors.

And that is particularly those who claim to speak for victims. So this, for me, really raises very deep questions about who has the right to tell someone else's story. Who has the authority to speak on behalf of someone else? And this is a little bit of a digression here, but for me, this really raises questions about the strategic consequences of packaging victims and victimhood in this way.

So we' get advocates and advocates, activists, always wanting to say things like, the victims want regime change. The victims want sewing machines. The victims want prosecutions of the perpetrators. But if you have this kind of hegemonic narrative in place, it's very easy to attack. All it takes is finding one victim who says something else and suddenly this narrative is called into question.

So for my money, failing to take account of the complexity of victims lived experiences not only is wrong on its face, but it also ultimately undermines a strategy to advocate on their behalf. So it's problematic for both moral and consequentialist reasons.

And this is as true for aid as it is for advocacy. You cannot empower someone if you have not bothered to figure out what is actually impeding their access to power. But the focus on these very simplified narratives with Western interveners at their center, makes understanding that basically impossible.

And this style of advocacy and aid is really deeply entrenched and reinforced by what I describe as a feedback loop of public attention and funding. So these stories that tell this very comfortable, familiar narrative about a white woman being awakened to misery elsewhere draw press coverage. Those stories on The New York Times got tons of views.

And that press coverage drives funding. So donors prefer to support the programs and activities that are going to attract media interest. And it's therefore no surprise that actors designing programming on the ground, whether they're international organizations or local activists, will frame their work in terms that they know it's going to get them money and press coverage.

So lather, rinse, repeat. This is how this all gets reinforced. And I want to conclude here by emphasizing that these dynamics constrain interveners as much as they limit the agency of beneficiaries. So the problem we're identifying in this report is not individual NGO's decision to hand out some goats or teach women to make beaded purses.

There's almost certainly situations where that's a totally reasonable thing to do. No, what we're calling attention to here, is a set of mutually reinforcing structures that make the distribution of sewing machines, of chickens, of cows, seem like the natural and best solution to every problem faced by women in the developing world. Thanks.

[APPLAUSE]

MICHELLE ENGLISH: We'll take questions now. You can line up behind the mics. [INAUDIBLE] introduce yourselves. Start with [INAUDIBLE].

AUDIENCE: Thank you, that was really insightful and important. I'm John Tirman of the Center for International Study. I wonder if your critique or your investigations include the boom in microcredit solutions to women's situations in the developing world.

There's been a lot of attention to this. There's been a lot of criticism. And yet, it continues to be an enormously robust enterprise worldwide, much of it backed by the same agencies you were talking about. The one criticism that I recall as being a major note of the knowledgeable critics who have voiced it, is that the funds, well, there are several about the structure of loans and so on.

But that in fact, the results, if you try to measure the results of microenterprise for women's empowerment, the results are scant. Such an enormous enterprise, that it's hard to conclude in such a brief way. But in any case, I wonder what your take is on this.

NIMMI GOWRINATHAN: Yeah, microcredit was, I was an aid worker from 2004 to 2015. I didn't intend to be an aid worker. I was working with young women who had come out of the Tigers in northeast Sir Lanka who were at an orphanage and the tsunami happened. Some you might not remember, December 2004 there was a massive tsunami.

And so I went back to support these orphanages that were all destroyed during that time. And ended up staying on to do quite a bit of humanitarian work. That was really the height of the microcredit. And what happens I think, is even when it's in one sphere, it quickly becomes a solution for everybody everywhere. So then it became a post tsunami thing that we should use microcredit.

The issues that I've seen with it, and again, speaking from a gender perspective, in the countries that I've worked, in Pakistan, in Sri Lanka, in Eritrea, in Afghanistan, almost always the allocation of funds directly to women puts them at greater vulnerability than they were before.

You will see increases of domestic violence in those conditions. In Pakistan and after the earthquake in Kashmir, we had a situation where after the earthquake, all of a sudden I got all these phone calls from everybody, we want to fund a girls' school, girls' school, girls' school. And it was like the earthquake happened the day before. There's no water, there's no nothing.

The only thing people wanted to fund was a girls' school. And it's again, one of these interventions that along the lines of gender and women's empowerment, there's no ability to understand the context around the school. She can't get to school because there are 15 military checkpoints to get there. You building a school does very little.

But in that environment, in that moment, all these NGOs came in and they said, we want to fund women, we want to fund microcredit, we want to fund women to run NGOs, all within week. Within two weeks, they had kicked out all of the NGOs, because they didn't want the men, there's no attention to the men in these areas.

The technical problems with microcredit, in Sri Lanka we saw somewhere around 26% interest rates. So outside of this technical problem, again, what we're saying in this report is, we need to draw the technical critique into the broader political critique. The political critique I would have of that is, when you have, in Sri Lanka, you have a post-conflict period, where essentially the Tamils are being occupied by the Sri Lankan military.

Now when the women are given loans, they're given by government banks that are tied to the military. So you're putting women into a position now that they're indebted, already they're in a position of deep vulnerability in a militarized zone where sexual violence is one of the primary things they're vulnerable to. Now they're indebted to the military, to the government.

They have something that they owe them, because they're all controlling this entire network. To me, it feels like this is largely being driven by corporations, by large banks. We've had donors like Honeywell Corporation, who refused to fund the tsunami in Sri Lanka because they didn't have a market there. So it wouldn't grow their market for them to give money in Sri Lanka.

But they wanted to give in India, and they wanted to give microcredit because they could slowly spread out in a country they were already operating into villages that were more and more remote and spread credit systems and banks in these different areas. So I think it has unique challenges for women, the microcredit programming. And it's not something I support. I don't know if Kate has any other--

KATE CRONIN-FURMAN: Yeah, the only thing I would add is just to say this is kind of exactly what we're talking about. There's this sense in part, driven by the kind of move towards metrics and to easy measurement and evaluation that we want clean, very discrete interventions that are one thing that we can put in place and very easily track what's happening.

And I think that's all so much delusion. There's no way to cleanly intervene into the circumstances of people's lives. There's no way to intervene in a way that doesn't interact with the existing power dynamics to which they're subject. And I think the kind of emerging evidence that microcredit doesn't help so much is exactly testament to this fact.

That even though it seems, OK, we'll avoid all of these messy issues by just giving them money and letting them do whatever they want with that money. We see that even that is taking place in the shadow of politics, in the shadow of the patriarchy, in the shadow of these women not really having free choice to do whatever they want with that money.

That even though it seems, OK, we'll avoid all of these messy issues by just giving them money and letting them do whatever they want with that money. We see that even that is taking place in the shadow of politics, in the shadow of the patriarchy, in the shadow of these women not really having free choice to do whatever they want with that money.

AUDIENCE: Hello, I'm Jarrod Goentzel from the MIT Center for Transportation and Logistics. And I direct the Humanitarian Supply Chain Lab there. As a researchers trained in engineering, I'm very comfortable with numerical evidence and that kind of argument, and I've learned over time the power of narrative. So my question's around that.

But I want to give an example. We have a project we're working in Uganda with a US aid mission there to analyze how market systems are changing. Looking at ways of, the different approaches to modifying evaluation, looking more systemically. And our new country strategy, systems is a part of this, part of, another pillar is resilience, another pillar is demographics.

And around demographics, they've framed a narrative that all of the activities are meant to have some connection with around what they call the median Uganda 14-year-old girl. And they position it so, the way of trying to unify all the different activities that could not be a single solution like micro-finance, but looking at all the different things.

How are we empowering or providing an opportunity for that girl to flourish? So they don't position her as a victim, but they do use the language like, she is in a fragile position. And they talk about a path forward that, according to probabilities, would not be one that. So how can we adjust the system to be more supportive of a productive path?

So that's an example of narrative being used to help unify the mission's activities. So I'm curious if you, I don't you don't know the situation well, but if you have comments on that narrative, and more generally, if you have examples of narratives that are productive in helping to target gender issues effectively.

NIMMI GOWRINATHAN: I would say, our co-author, who's a good friend of mine, often refers to this as a magician's sleight of hand. And I think that it happens quite often with women. One of the major issues is the siloing of development versus political spheres.

Gender is the first thing to be siloed into the development side. So when you have, let's say, "Human Development Report on Afghanistan" that I worked on for the UN, the women's issues are always on the development side. Otherwise, it's a politician or a certain number of women expected to be gender parity in parliament or something. And then those women become the ones who have to represent all women's issues.

This is part of the framing of all of this. And what it does is, that it allows for the political issues to never be dealt with. And it's done quite calculatedly I think. Because of the donor interests involved, I'll give you an example. I was doing a survey for the Asian Development Bank and UN Women.

It was a massive survey of Asia last year. Reasons why women would not be able to achieve the sustainable development goals, the barriers to that. Which is sort of an interesting project and it was something I wanted to explore. What was fascinating though, in this context is, that the state was sort of disappeared.

You're looking at the various risk factors and I'm given very, climate change and all these things that I'm supposed to analyze the impact on this woman, and the state doesn't exist in this analysis. And what's created as, in terms of this woman, the 14-year-old girl. This is the same language that's used by USAID and others.

There would be a reference to her identity. And they would say in this really horizontal way, that religious minority, indigenous whatever the category might be, untouchable, there's actually one government document that said et cetera in terms of the aspects of her identity are in this horizontal line.

The argument has to be that it is vertical. That each of these things deepens the impact of the other. If you're a Muslim, if you're Untouchable, if you're in this impoverished rural area, if you're vulnerable to climate change. But all of these things will be deepened by gender, always.

And in this type of analysis, you really have to understand identity. You have to understand identity and you have to understand the state. By the end of the analysis, UN Women and ADB came back to me and they said, it's good, it's really interesting. You need to take out India and take out the word identity. Identity can't be used in this. You have to use the word marker.

These are all ways to use gender to depoliticize what's being done. If I take India out, but nobody knows that I was told to take India out, then the report just goes out there in the world as if India is the only country that has no problems with gender. But this is a conversation that happened in the political space between the Indian government and UN Women. And they conceded to this conversation.

For me, a lot of the work that I do now is on the overt political mobilization of women. Women at City College, women in Sri Lanka. To me, that is the only, all of these other programs are not going to work unless there is political mobilization. And I don't think it's as drastic as people think it is. It scares donors, for sure. Because if you say, well, we're going to allow women to mobilize politically, I can't tell you what direction that's going to go in.

And if you can't determine the direction, then you don't know if you want to support that. I also can't show you the six little baby girl dresses that come out of a sewing machine at the end of the month. I can't show you progress in numbers. I can't show you any of that. But what we are trying to do, is when you have these spaces already, the sewing machines and the beauty salons, you start to have a political conversation in those spaces.

And I do see that starting to happen in Sri Lanka. I do see it. It's not something that can be measured. It's not something that I could write an Impact Report about or monitor and evaluate. But I can see it happening in the Northeast. And these are the kinds of things that terrify major organizations like USAID and UN.

KATE CRONIN-FURMAN: So I'm not familiar with the intervention that you're describing obviously, but it sounds like an attempt to be thoughtful about some of this stuff and try to do things in a different way. Unfortunately, what we've found is, that even those more thoughtful attempts are very much constrained by all of the dynamics that we're talking about here.

So we presented this report in September in Canada. And there was another woman on the panel with us who was a doctoral researcher in the UK, who had also, like both of us, been doing research in post-war Northeastern Sri Lanka. And she described an empowerment intervention that had been initiated by local actors.

It was extremely well-thought out, extremely careful about the intervention. Basically what they had said was, OK, we're sick of all this re-feminizing nonsense. Women don't want to make cakes, they don't want to sew. Let's help them to buy Tuk Tuk. So these are the three-wheelers that you use for public transport there. And they said, and we don't want to foster a culture of dependency.

So we're going to set up this loan scheme, where we're not giving them the Tuk Tuks, but it's not burdensome and they'll be able to repay it. So basically had gone down the checklist of all of the obvious problems with these types of empowerment interventions and attempted to preempt them in a way that was sensitive to the local culture and sensitive to what women's needs actually were.

So they had a pilot program. A number of women got these Tuk Tuks, everyone was really optimistic. Program completely failed. Despite all of this thoughtfulness, despite all this effort, this program was understandably simply unable to grapple with the legacies of women's multiply reinforcing experience of violence.

Some of these women were quite traumatized and were anxious about being out on their own. Others had families that were not willing to have them out at night. They weren't able to compete with their male counterparts, even with the assistance. And basically, this was very disheartening obviously, for the local organization that had set up this program. Because they thought they had hit on this solution.

It was OK, we're not falling into all of the classic traps of an empowerment intervention. So what we're arguing is that this isn't about the individual program. This isn't about the individual intervener. This is about the fact that it is simply not possible to empower women solely through this type of intervention.

NIMMI GOWRINATHAN: I would add here, since this is MIT, that I was teaching at Columbia this semester at the School of International and Public Affairs, and what's fascinating is, part of the problem is how we're educating those who are going into this field.

The restricted consciousness of these students, their limited ability to think outside of the frames that they have been given already to acknowledge that this is not working, but to only challenge that in so far as you stayed within what you've been told might be effective.

There was over and over again in my classes, we'd come up with these mind maps and just sort of-- And I would ask them, what happens if you just get rid of everything that you frame this with? Everything that you're trying to look at this through. Through all different kinds of lenses of helping people, of morality, of what's a threat and what's not a threat.

The way that people are being taught is so formulaic, is so problematic, that you're not able to start to understand some of these concerns. But without doing that, you can't get to the root of some of these issues. Sexual violence does not end because Ben Affleck goes to the Congo. It ends because there's political mobilization. Hasn't ended in this country, but it shifted drastically when there was political mobilization. Not because a celebrity showed up.

AUDIENCE: My questions are for Professor Gowrinathan. So you mentioned that under a lot of the way that these programs work is that women are conferred as agents when they challenge local culture, non-political structures. But considering the cultural norms that reinforce gender hierarchies are power structures in and of themselves, can you define a little more how you're defining culture versus politics in that context?

And in addition, I was wondering if you could explain a little bit more what you meant when you said NGOs can act in a repressive role when they occupy the space between the state and marginalized women. Just to flesh that out a little bit more.

NIMMI GOWRINATHAN: Yeah, in terms of culture, the argument that I'm making is that culture will always wrap around context. It's nearly impossible to extricate these two from each other. So if you're talking about a girl in Afghanistan whose father doesn't want her to go to school, maybe it's cultural. Maybe he doesn't believe girls could be educated.

More often than not, being in these spaces, which is again, one of the great challenges of this. People are not in these spaces doing field work. Being in these spaces, he's afraid that she might be raped on the way to school. Because there's so many military checkpoints there.

We don't know. We're not able to parse this out, but we cannot blame all of it on culture. Because there's an aspect to that that is context. And the context, the contextual aspect of it, is the part that outsiders have the ability to challenge. And it gets complicated.

In a recent paper that I wrote with a colleague, it looks at women under the Tigers. The Tigers were considered to be sort of fascist in controlling their territory as a movement. And what it argues, is that the search for agency is often misplaced. You're looking for the women standing outside with the placards. You're looking for the women running for Parliament. You're looking for the Malalas of the world.

She has to be either a superhero or a victim. But you have agency in these spaces, and it's really important to find the agency, to look in the right places. If you have a woman let's say in Sri Lanka, there was women who would feign pregnancy to be able to get into the detention center, so they could see their husbands, they could pass on information of what was happening in the moment.

This is an overtly political act. It is a form of agency. They are playing on cultural expectations, cultural norms in order to create that political space for themselves. But that is a form of agency. And if you don't keep locating these pockets of agency where we believe it doesn't exist, where we believe the culture prevents it from existing, then what you have is an expectation like right now in the Northeast, that without the Tigers, there's no political voice. Because there was never a political space.

There's always political space. Women are always finding ways to make a political space. So with agency and culture, it's only to caution that culture is not always the perpetrator. And when it is, those are conversations that happen within the community. They cannot be had by the UN or the US government or anybody else. And I'm sorry, the second part of your question was on?

AUDIENCE: NGOs being in the space between the state and marginalized women. Just kind of what--

NIMMI GOWRINATHAN: Right. It's, this idea that NGOs like to be both the powerful and the powerless, and they don't get to occupy both spaces. They are a very powerful industry collectively. The example I can give you is that when I did the UN Human Development Report for Afghanistan, it was supposed to be, the first time it was focused just on gender.

NIMMI GOWRINATHAN: Right. It's, this idea that NGOs like to be both the powerful and the powerless, and they don't get to occupy both spaces. They are a very powerful industry collectively. The example I can give you is that when I did the UN Human Development Report for Afghanistan, it was supposed to be, the first time it was focused just on gender.

And the only way to look at women in Afghanistan is to say, OK, here's the state, here's women. And there's this massive humanitarian apparatus that's mediating this conversation. There's no other way to look at the positioning of women. I can't write a paper for you about the position of women without acknowledging who's mediating that conversation between the state and the individual women.

And Afghanistan is one of the most obvious examples of this. So when the NGOs say that their goal is to help the women that the state would not have looked at, the state is very happy to have the NGO play that role, because they're reinforcing a kind of positioning for those women in those populations that they will always be dependent. They will always not have political power.

So the NGOs, it's the positioning that they have. The difference with NGO-ization is, NGO-ization says that the state's just given up or left behind. My argument is, most of the time the state is calculatedly keeping people in a position far away from power.

AUDIENCE: My name is [INAUDIBLE]. And I am from Heller School of Social Policy. So my question to you is, Dr. Gowrinathan, you started your presentation with some kind of personal dilemma that you've been facing as a development worker. But as someone, as a development practitioner from the global south, sometimes you think that you are being [INAUDIBLE].

So I think the same. These are like the thoughts that keep me awake at the middle of the night. So how do you still, like, go with that? That's the first thing. And the second thing is, what would be your advice for those of you-- for those of us that are young professionals in the development world? Thank you.

NIMMI GOWRINATHAN: I think it's a really valuable role that you have to play. But you have to insist on the space to play it. I call the space kind of an inside outside. You don't fully belong in either space. There was moments at the end of the war in Sri Lanka where I was running the Sri Lanka working group of everybody trying to coordinate humanitarian efforts, and everybody thought I was a spy for the Tigers, that I asked for something.

And there's moments when I'm in the Northeast of Sri Lanka and they can only see you as a Western person who gives funds, or they don't trust you. But I think being able to draw on these multiple spaces gives you an ability to create insight that other people can't have, that other people don't have.

And it's not easy to articulate that. Especially in a field, like I did my PhD in political science. That was very difficult, that process, to insist that the insights that I had, the intimate knowledge of culture and community were intellectually valuable. Initially, I had to frame everything in the language and the patterns and the measures that they gave me, and in their language, in order to get past that point.

And as you get past each point of essentially credibility, you get to break down a little bit of that. You get to move further and further outside of that. The program we're running at City College comes out of this idea. It is to train immigrant women to be a scholar or activist.

To say that you are the ones from Afghanistan, from Somalia, from all of these places. Whenever there's a conflict, we see a spike at City College of students coming in to the school. I don't want to sit in the US Institute of Peace anymore and listen to white women tell me about these countries.

I want to hear you tell me about your experiences and draw that into your research. Have identity-driven research agendas. I think it's really, really valuable. The best advice I can give you is to write. To write throughout your experiences. Your critiques, your feelings. Because all of that turns into something.

There's moments from my early days in the humanitarian world where I heard all kinds of things that were deeply problematic. That are now in the book that's coming out. So hold onto those and write for yourself, for catharsis as much as anything else. And I think, and I would want Kate to comment on this too, part of this report is to reveal the role that race plays in everything.

In the CVE world, we talk about it a little bit, and we haven't gone into it, but one of the damaging things about this empowerment approach is that it's now seeped into the Countering Violent Extremism world. And the female fighter is just another one of these damaged normal projects.

And in that space, there is a woman who is very powerful in international studies. And we argue, Rufia and I and Kate and others, that what's driving foreign policy, the feminism allowed in foreign policy, where there is feminism allowed, is a white feminism. And that's really problematic. Because you're dealing mostly with women of color in the developing world.

And after this report was published, we got an email from this woman that said, who I've been arguing with for four or five years in different spaces and conferences and Congress and she's a conservative sort of thinker and violent extremism, and we would always debate in all these different spaces.

And then she sent this email that essentially said, be careful not to alienate the white allies that you need. And I realized all of a sudden, that her and I haven't been debating violent extremism all these years. We haven't been debating the female fighter or gender in violence or theories of gender. It's been race. That's what it was.

And it's a conversation nobody wants to have. We were still relying on the Swanee Hunt, Valerie Hudson version of the world. In foreign policy, there's very few women of color. So I think it's important to keep bringing up that race is at the core of a lot of this. And I'd want to hear Kate's thoughts too on this.

KATE CRONIN-FURMAN: Yeah, there's a way in which in both academia and the policy world what brown people tell us is never theory, it's always evidence. And I was having drinks with a Sri Lankan Tamil colleague in London last week actually, and he's also a PhD in political science.

And he told me a story about when he was doing his doctoral work, having a conversation with a senior white professor colleague about Sri Lankan politics. And he advanced a theory explaining patterns of rural support to a particular political party.

And later saw himself quoted in the colleague's works cited, anonymous Tamil activist interview. This was a PhD student at a prestigious London institution advancing a political theory. And yet he was cited as data by his own colleague. And that's obviously flatly ridiculous.

But he went on to get the PhD and get hired by that institution. And now he's on an equal footing with the person who did that, and describes the reason for pursuing this PhD being so that he wouldn't always be treated as evidence. That he would be able to opine on the politics of his own country and be taken seriously.

And I think when you say you weren't debating politics, you weren't debating theories of violent extremism, I think part of what you were debating was your authority to speak on this as a person associated with one of these contexts where the interventions are going.

And so I think this is what's wonderful about the City College program, about Beyond Identity, is that we need to get rid of this perception that there's such a thing as a neutral opinion and that it only comes from someone with a white face. None of us are neutral, none of us are objective on anything ever.

And so everyone has to be allowed to speak. And unfortunately, the only way to make that happen is for people who are currently not allowed to speak, to push back and push back hard.

NIMMI GOWRINATHAN: And I want to be clear. This isn't a million years ago, this is like--

KATE CRONIN-FURMAN: Oh, yeah, this story happened two years ago.

NIMMI GOWRINATHAN: At Columbia in the fall, I gave a lecture. A number of students went to the dean and said that they didn't think that I was a credible speaker and I shouldn't have been allowed. And I had a student come to me from Yale last year, who was told she can't study Sri Lanka because one, or sexual violence in Sri Lanka, one, sexual violence is the least important aspect of conflict.

And two, because she was Sri Lankan. And it's almost verbatim what I was told at UCLA. That I couldn't study Sri Lanka because I wouldn't be objective. So it's not an uncommon experience.

KATE CRONIN-FURMAN: But you know if you were studying Russia, people would be like. but don't you want to study South Asia?

NIMMI GOWRINATHAN: Yeah, probably. Yeah, so there's others, but you just have to, you really do have to have the platform. Otherwise, nobody will listen.

AUDIENCE: Hello. Thank you for all of your insight so far. My question deals with philosophy of whether you think it's better to redefine the current mindset or create something entirely new. So do you think it would be more effective to change the paradigm of existing NGOs? Or what ideas do you have of alternative vehicles of social justice that would either be independent of NGOs or work in conjunction with them?

KATE CRONIN-FURMAN: Yeah, so I think this was maybe Nimmi's point about not wanting to get down into the weeds of solutions. Because as yet, we haven't really been able to have the conversation acknowledging the problem. And what I'll say here, is that what we're calling for in this report is essentially revolution.

We need to recognize that actually empowering women is going to be difficult. It's going to combat entrenched power dynamics. And that it requires supporting them through the messiness that that will produce. And I just want to say, looking at what's happening here now, I mean look at it the me too moment.

This is an instance in which some women are taking some power that was previously denied to them. These are white women. Many of them are famous women. They're beautiful women. They're wealthy women. They're women who have the platform of The New York Times and every other major media organization on the planet. And still, look at the pushback.

And as if this is what it looks like when the most privileged women on earth start to demand some modicum of empowerment, start to challenge existing structures of repression, how much harder is it going to be when they are marginalized women of color in other countries? So I think, no, we're not talking about making minor changes to existing structures. We're talking about a wholly different approach.

NIMMI GOWRINATHAN: Yeah, and I think it's challenging underlying assumptions about gender. The idea that women are more peaceful. The idea that if women are, people really say it outright like that anymore, but use code words, like women are democratic. None of that is true.

And it's creating the political space to say that if we're going to include; I've been a part of peace talks where they'll be a sort of six seats for women, which this is the big focus of women's empowerment, to have those seats there. That the seats have already been labeled on the back in terms of what their politics are.

They have to be peaceful. They have to be progressive. They have to be democratic. You don't create peace by having a certain type of Benneton picture. You create peace by having a diversity of opinions. So you have to have the women who fought in the Tigers, the women who are Muslim hardliners, the women who are, the opinions that you don't want to hear.

I think until you can shift political spaces, the NGO world will necessarily mimic the political spaces, because the incentives are so tied to each other. There are things that are happening. I don't know, again, I hesitate to name them or to, but there is, this summer there'll be a collective of activist movements in Africa.

And it's to me, really interesting, because they refused to take any NGO funding at all from anybody. And they've managed to figure out a way to all meet in West Africa to discuss a collective plan for activism. And the idea is to do similar things in the US and other spaces.

In terms of tangible spaces, I actually think Europe is far ahead of the US in terms of thoughtfulness on these questions. But no, it's the NGO model is pretty well entrenched. I think it requires a restructuring of how we understand gender fundamentally to allow that political space.

AUDIENCE: Thank you.

AUDIENCE: My name is [INAUDIBLE]. I'm a student at Heller School for Social Policy and Management. And I'm also at the [INAUDIBLE]. I don't have a question, but I want to share my experience with you in the issue of representation of women, the media and the narrative of victimization.

So I suffered from gender-based violence since I was 11 years old. Also in 2011, after my participation in the revolution, I was arrested, tortured, sexually assaulted. And recently, I was sentenced to life imprisonment, and I was forced to leave my country. My story was featured in a documentary here in the United States.

And I have an issue with the representation of women, which is matter for all feminists, especially those who are [? anti-colonial ?] and anti-racism. So in my case, as a representation was to [? reducted, ?] they focused much about the victimization part to show how much violence I faced in my story.

But the documentary, for example, neglected the part, the powerful part of me as a woman. They focused on how much violence we are facing, but how much powerful, I see that that is not represented well in the documentary. And also I feel like no, like, woman has a right to craft or edit their representation in the media or in the academic or artistic work or those, the people who choose to representation them ask us how we would like to be represented.

Which part of our stories we want to tell. For example, people who know my story will obviously ask why they neglected this part of your story, because people who started to know my story in Egypt because of this part they described as powerful part, but this [INAUDIBLE] at all in this documentary. So people start to ask why this wasn't [INAUDIBLE].

So I feel like the [INAUDIBLE] representation and they focus much on the victimization part . That's why through my being here, I try to show that Muslim women or African women, we are facing the violence, but we are powerful. We are fighter. And we are not only victim to our own men, our own society, our own government, but we are fighting with other men and women this patriarchy society for our freedom and justice. Thank you.

[APPLAUSE]

NIMMI GOWRINATHAN: Thank you so much for that. For me, it's one of the things that requires what we were talking about. This deconstruction of how we think. There's this automatic assumption that visibility and awareness is politically useful. It is not. And what happens is, that nobody ever wants to close the loop. I mean, nobody's been able to do it for me.

This idea that you can show people in Nebraska what's happening in Darfur and you can use this one woman, it has never been proven to lead to political change. We are all operating on this false momentum that after everybody knows about it, then what? Rarely does this ever--

KATE CRONIN-FURMAN: Push the big red button that says fasten.

NIMMI GOWRINATHAN: There's no, there's red bracelets, there's campaigns, there's hashtags. These things, awareness and visibility become really problematic, and they become attached to the idea of how we engage with other communities. There was documentary that I very mistakenly was a part of with Vice News in Sri Lanka.

And I bought into this idea of everybody was like, oh your work is so good and you need a bigger audience and a bigger audience. And going back with these journalists to Northeastern Sri Lanka, we were doing a story on ex-combatants who had turned into prostitutes.

The series was on women in and at war. And for me, it was really important to start to show in the media, the complexity of women's politics in these contexts. And that violence actually shapes women's politics in really unique ways. And so what it was like for this woman as an ex-combatant to now be a prostitute to soldiers, is what we were trying to reveal.

Obviously, they didn't want their faces shown. Obviously it was difficult for them. And the journalist said, before we interviewed this woman, who we knew had been raped, who we knew was a soldier, or ex-combatant, don't tell her that she can cover her face.

And I looked at her and I said, I need you to think this all the way through. You don't cover her face, your program actually gets watched by 50 million people globally. They find out she's told she was raped, she gets tortured, probably killed. Who's responsible for that?

But your assumption that we're going to help her, her cause by visibility, this becomes this underlying driving force. Visibility in itself becomes the motivation. But there's nothing on the other end of that. You see it over and over again. When I was in Tunisia, I saw it in the tribunals that were happening. It was just, OK, let's bring all the women out and talk about sexual violence.

But on the other side, I was interviewing these women's daughters who were the highest number of recruits to ISIS. Why? Because they didn't like that their moms were publicly going out there. They thought the activism was too soft. That they were going back to the state and becoming victims, when they should have been political agents.

This process in itself may have led to the mobilization of young women to join ISIS. And what came out of it, a lot of visibility. So I think it's one of those things, particularly those of you going into the development field, have to start off questioning, what is the role of visibility. Why do we do it?

AUDIENCE: Hi, my name's Ellie. I'm in history and sociology of science here, previously in political science. And I spent some time in Somalia doing work like this and my experiences completely agree with what you're writing about. And many of my conversations with friends who were there are in line with that. But I'm curious how and when do you find your arguments are persuasive to people who work in development who don't have personal experience of this?

KATE CRONIN-FURMAN: We've been really surprised at how little pushback there's been on the analysis. I mean, people obviously don't want to have to think about making dramatic changes. But by and large, I think these are things that people working in the industry know.

So I, for years, have blogged about this stuff at "Wronging Rights." And from the earliest days when we started that blog 10 years ago, we were constantly getting emails from people pretty high up at the organizations that are exactly the ones perpetuating this framework, saying, giving us tips on appalling things their own organization was doing.

So it's not that people don't know this. It's not that even, I'm sure there are true believers obviously. But I think by and large, there's a lot of agreement that the way we're doing things isn't great. But obviously, it's hard to envision systematic change. It's hard to figure out what that would look like. So I've not really felt like we've needed to do so much persuading, as that this has more played the role of catharsis in a lot of way. I don't know--

NIMMI GOWRINATHAN: I will say there's been some cherry picking of the argument.

KATE CRONIN-FURMAN: Yes.

NIMMI GOWRINATHAN: And that's problematic. One of the feminist groups in New York, there's a feminist collective who's interested in these issues, and someone who is on the list sort of came and told me this report circulated and everyone does that. So what's really interesting about the conversation is that everybody agrees that the programming is depoliticizing. And they like that focus.

Nobody has acknowledged the role of white feminism in that. So again, if you don't see the argument as a whole, you're not going to be able to get to the shifts that you want to see. And I know from being inside the industry for a long time, there's a real I think unsubstantiated fear of what happens to donations when you offer any sort of critique.

So there is constantly, we were told not to critique the Red Cross in Sri Lanka, we were told not to critique, I mean, just overt requests not to do this, lest one shake donor confidence. I don't think it's true. I've worked with a lot of donors. And I think that if you got rid of the word empowerment entirely, and you had to go back to the Gates Foundation or to any of these individual donors and say how you actually shifted the individual, community, family, state level power dynamics that are restricting this woman the concentric circles of captivity she's under, if you had to go back and say that and you didn't have this catch-all word to use, you would have to actually be doing something.